|

© Victor & Victoria Trimondi

The

Shadow of the Dalai Lama – Part I – 2. Tantric Buddhism

2. TANTRIC BUDDHISM

The fourth and final phase of Buddhism entered the

world stage in the third century C.E.

at the earliest. It is known as Tantrayana, Vajrayana or Mantrayana: the “Tantra

Vehicle”, the “Diamond Path” or the “Way of the Magic Formulas”. The

teachings of Vajrayana

are recorded in the holy writings, known as tantras. These are secret

occult doctrines, which — according to legend — had already been composed

by Buddha Shakyamuni, but the time was not deemed

ripe for them to be revealed to the believers until a thousand years after

his death.

It is true that Vajrayana basically adheres

to the ideas of Mahayana

Buddhism, in particular the doctrine of the emptiness of all appearances

and the precept of compassion for all suffering beings, but the tantric

temporarily countermands the high moral demands of the “Great Vehicle” with

a radical “amoral” behavioral inversion. To achieve enlightenment in this

lifetime he seizes upon methods which invert the classic Buddhist values

into their direct opposites.

Tantrism designates itself the highest level of the entire

edifice of Buddhist teachings and establishes a hierarchical relation to

both previous phases of Buddhism, whereby the lowest level is occupied by Hinayana and

the middle level by Mahayana. The

holy men of the various schools are ranked accordingly. At the base rules

the Arhat,

then comes the Bodhisattva, and

all are reigned over by the Maha Siddha, the tantric Grand Master.

All three stages of Buddhism currently exist alongside one another as

autonomous religious systems.

In the eighth century C.E., with the support of the Tibetan dynasty of the

time, Indian monks introduced Vajrayana into Tibet, and since then it has

defined the religion of the “Land

of Snows”. Although

many elements of the indigenous culture were integrated into the religious

milieu of Tantric Buddhism, this was never the case with the basic texts.

All of these originated in India.

They can be found, together with commentaries upon them, in two canonical

collections, the Kanjur

(a thirteenth-century translation of the words of Buddha) and the Tanjur (a

translation of the doctrinal texts from the fourteenth century). Ritual

writings first recorded in Tibet

are not considered part of the official canon. (This, however, does not

mean that they were not put to practical use.)

The explosion of sexuality: Vajrayana Buddhism

All tantras are

structurally similar; they all include the transformation of erotic love

into spiritual and worldly power. [1]

The essence of the entire doctrine is, however, encapsulated in the

so-called Kalachakra Tantra, or

“Time Tantra”, the analysis of which is our

central objective. It differs from the remaining tantra

teachings in both its power-political intentions and its eschatological

visions. It is — we would like to hypothesize in advance — the instrument

of a complicated metapolitics which attempts to

influence world events via the use of symbols and rites rather than the

tools of realpolitik.

The “Time Tantra” is the particular secret

doctrine which primarily determines the ritual existence of the living

Fourteenth Dalai Lama, and the “god-king’s” spiritual world politics can be

understood through a knowledge of it alone.

The Kalachakra Tantra marks the close of the creative phase of Vajrayana’s history in the tenth century. No further

fundamental tantra texts have been conceived

since, whilst countless commentaries upon the existing texts have been

written, up until the present day. We must thus regard the “Time Tantra” as the culmination of and finale to Buddhist Tantrism. The other tantric texts which we cite in this

study (especially the Guhyasamaya Tantra, the Hevajra Tantra and the Candamaharosana Tantra),

are primarily drawn upon in order to decipher the Kalachakra Tantra.

At first glance the sexual roles seem to have

changed completely in Tantric Buddhism (Vajrayana). The contempt for

the world of the senses and degradation of women in Hinayana, the asexuality and

compassion for women in Mahayana,

appear to have been turned into their opposites here. It all but amounts to

an explosion of sexuality, and the idea that sexual love harbors the secret

of the universe becomes a spectacular dogma. The erotic encounter between

man and woman is granted a mystical aura, an authority and power completely

denied it in the preceding Buddhist eras.

With neither timidity nor dread Buddhist monks now

speak about “venerating women”, “praising women”, or “service to the female

partner”. In Vajrayana,

every female being experiences exaltation rather than humiliation; instead

of contempt she enjoys, at first glance, respect and high esteem. In the Candamaharosana Tantra

the glorification of the feminine knows no bounds: “Women are heaven; women

are Dharma; ... women are Buddha; women are the sangha;

women are the perfection of wisdom”(George, 1974,

p. 82).

The spectrum of erotic relations between the sexes

ranges from the most sublime professions of courtly love to the coarsest

pornography. Starting from the highest rung of this ladder, the monks

worship the feminine as “perfected wisdom” (prajnaparamita), “wisdom

consort” (prajna),

or “woman of knowledge” (vidya). This spiritualization of the woman corresponds,

with some variation, to the Christian cults of Mary and Sophia. Just as

Christ revered the “Mother of God”, the Tantric Buddhist bows down before

the woman as the “Mother of all Buddhas”, the

“Mother of the Universe”, the “Genetrix”, the

“Sister”, and as the “Female Teacher”(Herrmann-Pfand,

1992, pp. 62, 60, 76).

As far as sensual relationships with women are

concerned, these are divided into four categories: “laughing, regarding, embracing,

and union”. These four types of erotic communication form the pattern for a

corresponding classification of tantric exercises. The texts

of the Kriya Tantra

address the category of laughter, those of the Carya Tantra that of the look, the Yoga Tantra

considers the embrace, and in the writings of the Anuttara Tantra (the Highest Tantra) sexual union is addressed. These

practices stand in a hierarchical relation to one another, with laughter at

the lowest level and the tantric act of love at the highest.

In Vajrayana the latter becomes a religious concern of the

highest order, the sine qua non

of enlightenment. Although homosexuality was not uncommon in Buddhist

monasteries and was occasionally even regarded as a virtue, the “great

bliss of liberation” was fundamentally conceived of as the union of man and

woman and accordingly portrayed in cultic images.

However, both tantric partners encounter one

another not as two natural people, but rather as two deities. “The man

(sees) the woman as a goddess, the woman (sees) the man as a god. By

joining the diamond scepter [phallus] and lotus [vagina], they should make

offerings to each other” we read in a quote from a tantra

(Shaw, 1994, p. 153). The sexual relationship is fundamentally ritualized:

every look, every caress, every form of contact is given a symbolic

meaning. But even the woman’s age, her appearance, and the shape of her

sexual organs play a significant role in the sexual ceremony.

The tantras describe

erotic performances without the slightest timidity or shame. Technical

instructions in the dry style of sex manuals can be found in them, but also

ecstatic prayers and poems in which the tantric master celebrates the

erotic love of man and woman. Sometimes this tantric literature displays an

innocent joie de vivre. The

instructions which the tantric Anangavajra offers

for the performance of sacred love practices are direct and poetic: “Soon

after he has embraced his partner and introduced his member into her vulva,

he drinks from her lips which are dripping with milk, brings her to coo

tenderly, enjoys rich pleasure and lets her thighs tremble.” (Bharati, 1977, p. 172)

In Vajrayana sexuality is the event upon which all is

based. Here, the encounter between the two sexes is worked up to the pitch

of a true obsession, not — as we shall see — for its own sake, but rather

in order to achieve something else, something higher in the tantric scheme

of things. In a manner of speaking, sex is considered to be the prima materia,

the raw primal substance with which the sex partners experiment, in order

to distill “pure spirit” from it, just as high-grade alcohol can be

extracted from fermented grape must. For this reason the tantric master is

convinced that sexuality harbors not just the secrets of humanity, but also

furnishes the medium upon which gods may be grown. Here he finds the great

life force, albeit in untamed and unbridled form.

It is thus impossible to avoid the impression that

the “hotter” the sex gets the more effective the tantric ritual becomes.

Even the most spicy obscenities are not omitted

from these sacred activities. In the Candamaharosana Tantra

for example, the lover swallows with joyous lust the washwater

which drips from the vagina and anus of the beloved and relishes without

nausea her excrement, her nasal mucus and the remains of her food which she

has vomited onto the floor. The complete spectrum of sexual deviance is

present, even if in the form of the rite. In one text the initiand calls out masochistically: “I am your slave in

all ways, keenly active in devotion to you. O Mother”, and the “goddess” —

often simulated by a prostitute — answers, “I am called your mistress!”

(George, 1974, pp. 67-68).

The erotic burlesque and the sexual joke have also

long been a popular topic among the Vajrayana monks

and have, up until this century, produced a saucy and shocking literature

of the picaresque. Great peals of laughter are still heard in the Tibetan

lamaseries at the ribald pranks of Uncle Dönba,

who (in the 18th century) dressed himself up as a nun and then spent

several months as a “hot” lover boy in a convent. (Chöpel,

1992, p. 43)

But alongside such ribaldry we also find a

cultivated, sensual refinement. An example of this is furnished by the

astonishingly up-to-date handbook of erotic practices, the Treatise on Passion, from the pen of

the Tibetan Lama Gedün Chöpel

(1895–1951), in which the “modern” tantric discusses the “64 arts of love”.

This Eastern Ars Erotica dates from the 1930s. The

reader is offered much useful knowledge about various, in part fantastic

sexual positions, and receives instruction on how to produce arousing

sounds before and during the sexual act. Further, the author provides a

briefing on the various rhythms of coitus, on special masturbation

techniques for the stimulation of the penis and the clitoris, even the use

of dildos is discussed. The Tibetan, Chöpel, does

not in any way wish to be original, he explicitly makes reference to the

world’s most famous sex manual, the Kama

Sutra, from which he has drawn most of his ideas.

Such permissive “books of love” from the tantric

milieu are no longer — in our enlightened era, where (at least in the West)

all prudery has been superseded — a spectacle which could cause great

surprise or even protest. Nonetheless, these texts have a higher

provocative potential than corresponding “profane” works, in which

descriptions of the same sexual techniques are otherwise to be found. For

they were written by monks for monks, and read and practiced by monks, who

in most cases had to have taken a strict oath of celibacy.

For this reason the tantric Ars Erotica even today awake a great curiosity and throw up

numerous questions. Are the ascetic basic rules of Buddhism really

suspended in Vajrayana?

Is the traditional disrespect for women finally surmounted thanks to such

texts? Does the eternal misogyny and the denial of

the world make way for an Epicurean regard for sensuality and an

affirmation of the world? Are the followers of the “Diamond Path” really

concerned with sensual love and mystical partnership or does erotic love

serve the pursuit of a goal external to it? And what is this goal? What

happens to the women after the ritual sexual act?

In the pages which follow we will attempt to

answer all of these questions. Whatever the answers may be, we must in any

case assume that in Tantric Buddhism the sexual encounter between man and

woman symbolizes a sacred event in which the two primal forces of the

universe unite.

Mystic sexual love and cosmogonic

erotic love

In the views of Vajrayana all phenomena of

the universe are linked to one another by the threads of erotic love.

Erotic love is the great life force, the prana which flows through the

cosmos, the cosmic libido. By erotic here we mean heterosexual love as an

endeavor independent of its natural procreative purpose for the provision

of children. Tantric Buddhism does not mean this qualification to say that

erotic connections can only develop between men and women, or between gods

and goddesses. erotic love is all-embracing for a

tantric as well. But every Vajrayana practitioner is convinced that the erotic

relationship between a feminine and a masculine principle (yin–yang) lies at the origin of all

other expressions of erotic love and that this origin may be experienced

afresh and repeated microcosmically in the union of a sexual couple. We

refer to an erotic encounter between man and woman, in which both

experience themselves as the core of all being, as

“mystic gendered love”. In Tantrism, this

operates as the primal source of cosmogonic

erotic love and not the other way around; cosmic erotic love is not the

prime cause of a mystical communion of the sexes. Nonetheless, as we shall

see, the Vajrayana

practices culminate in a spectacular destruction of the entire male-female

cosmology.

Suspension of opposites

But let us first return to the apparently healthy

continent of tantric eroticism. “It is through love and in view of love

that the world unfolds, through love it rediscovers its original unity and

its eternal non-separation”, a tantric text teaches us (Faure, 1994, p.

56). Here too, the union of the male and female principles is a constant

topic. Our phenomenal world is considered to be the field of action of

these two basic forces. They are manifest as polarities in nature just as

in the spheres of the spirit. Each alone appears as just one half of the

truth. Only in their fusion can they perform the transformation of all

contradictions into harmony. When a human couple remember

their metaphysical unity they can become one spirit and one flesh. Only

through an act of love can man and woman return to their divine origin in

the continuity of all being. The tantric refers to this mystic event as yuganaddha,

which literally means ‘united as a couple’.

Both the bodies of the lovers and the opposing

metaphysical principles are united. Thus, in Tantrism

there is no contradiction between erotic and religious love, or sexuality

and mysticism. Because it repeats the love-play between a masculine and a

feminine pole, the whole universe dances. Yin and yang, or yab and yum in Tibetan, stand at the

beginning of an endless chain of polarities, which proves to be just as

colorful and complex as life itself.

The divine couple in Tantric Buddhism:

Samantabhadra and Samantabhadri

The “sexual” is thus in no way limited to the

sexual act, but rather embraces all forms of love up to and including agape. In Tantrism

there is a polar eroticism of the body, a polar eroticism of the heart, and

sometimes — although not always — a polar eroticism of the spirit. Such an

omnipresence of the sexes is something very specific, since in other

cultures “spiritual love” (agape),

for example, is described as an occurrence beyond the realm of yin and yang. But in contrast Vajrayana shows us how heterosexual erotic love can

refine itself to lie within the most sublime spheres of mysticism without

having to surrender the principle of polarity. That it is nonetheless

renounced in the end is another matter entirely.

The “holy marriage” suspends the duality of the

world and transforms it into a “work of art” of the creative polarity. The

resources of our discursive language are insufficient to let us express in

words the mystical fusion of the two sexes. Thus the “nameless” rapture can

only be described in words which say what it is not: in the yuganaddha, “there is neither affirmation nor

denial, neither existence nor non-existence, neither non-remembering nor

remembering, neither affection nor non-affection, neither the cause nor the

effect, neither the production nor the produced, neither purity nor

impurity, neither anything with form, nor anything without form; it is but

the synthesis of all dualities” (Dasgupta, 1974,

p. 114).

Once the dualism has been overcome,

the distinction between self and other becomes irrelevant. Thus, when man

and woman encounter one another as primal forces, “egoness

[is] lost, and the two polar opposites fuse into a state of intimate and

blissful oneness” (Walker, 1982, p. 67). The tantric Adyayavajra

described this process of the overcoming of the self as the “highest spontaneous common feature” (Gäng, 1988, p. 85).

The co-operation of the poles now

takes the place of the battle of opposites (or sexes). Body and spirit,

erotic love and transcendence, emotion and intellect, being (samsara) and

not-being (nirvana) become

married. All wars and disputes

between good and evil, heaven and hell, day and

night, dream and reality, joy and suffering, praise and contempt are

pacified and suspended in the yuganaddha. Miranda Shaw, a religious scholar of the

younger generation, describes “a Buddha couple, or male and female

Buddha in union ... [as] an image of unity and blissful concord between the

sexes, a state of equilibrium and interdependence. This symbol powerfully

evokes a state of primordial wholeness an

completeness of being.” (Shaw, 1994, p. 200)

But is this state identical to the unconscious ecstasy

we know from orgasm? Does the suspension of opposites occur with both

partners in a trance? No — in Tantrism god and

goddess definitely do not dissolve themselves in an ocean of

unconsciousness. In contrast, they gain access to the non-dual knowledge

and thus discern the eternal truth behind the veil of illusions. Their deep

awareness of the polarity of all being gives them the strength to leave the

“sea of birth and death” behind them.

Divine erotic love thus leads to enlightenment and

salvation. But it is not just the two partners who experience redemption,

rather, as the tantras tell us, all of humanity

is liberated through mystical sexual love. In the Hevajra-Tantra, when the goddess Nairatmya,

deeply moved by the misery of all living creatures, asks her heavenly

spouse to reveal the secret of how human suffering can be put to an end,

the latter is very touched by her request. He kisses her, caresses her,

and, whilst in union with her, he instructs her about the sexual magic yoga

practices through which all suffering creatures can be liberated (Dasgupta, 1974, p. 118). This “redemption via erotic

love” is a distinctive characteristic of Tantrism

and only very seldom to be found in other religions.

Cultic worship of the

sexual organs

What symbols are used to express this creative

polarity in Vajrayana? Like many other cultures Tantric

Buddhism makes use of the hexagram, a combination of two triangles. The

masculine triangle, which points upward, represents the phallus, and the

downward-pointing, feminine triangle the vagina. Both of these sexual

organs are highly revered in the rituals and meditations of Tantrism.

Another highly significant symbol for the

masculine force and the phallus is a symmetrical ritual object called the vajra. As the

divine virility is pure and unshakable, the vajra is described as a

“diamond” or “jewel”. As a “thunderbolt” it is one of the lightning

symbols. Everything masculine is termed vajra. It is thus no surprise

that the male seed is also known as vajra. The Tibetan translation of the Sanskrit word is dorje, which also has additional

meanings, all of which are naturally associated with the masculine half of

the universe. The Tibetans term

the translucent colors of the sky and firmament dorje. Even in pre-Buddhist times the peoples of the Himalayas worshipped the vault of the heavens as

their divine Father.

Vajra and Gantha

(bell)

The female counterpart to the vajra is the lotus blossom (padma) or the

bell (gantha).

Accordingly, both padma

and gantha represent the vagina (yoni). It may come as a surprise to

most Europeans how much reverence the yoni

is accorded in Tantrism. It is glorified as

the “seat

of great pleasure” (Bhattacharyya, 1982, p. 228). In “the lap of the diamond woman” the yogi finds

a “location of security, of peace and calm and, at the same time, of the

greatest happiness” (Gäng, 1988, p. 89). “Buddhahood resides in the female sex

organs”, we are instructed by another text (Stevens, 1990, p. 65). Gedün Chöpel has

given us an enthusiastic hymn to the pudenda: “It is raised up like the

back of a turtle and has a mouth-door closed in by flesh. ... See this

smiling thing with the brilliance of the fluids of passion. It is not a

flower with a thousand petals nor a hundred; it is

a mound endowed with the sweetness of the fluid of passion. The refined

essence of the juices of the meeting of the play of the white and red

[fluids of male and female], the taste of self-arisen honey is in it.” (Chöpel, 1992, p. 62). No wonder, with such hymns of praise, that a regular sacred service in honor of the

vagina emerged. This accorded the goddess great material and spiritual

advantages. “Aho!”, we

hear her call in the Cakrasamvara Tantra,

“I will bestow supreme success on one who ritually worships my lotus [vagina], bearer of all bliss” (Shaw, 1994, p. 155).

This high esteem for the female sexual

organs is especially surprising in Buddhism, where the vagina is after all

the gateway to reincarnation, which the tantric strives with every means to

close. For this reason, for all the early Buddhists, irrespective of

school, the human birth channel counted as one of the most ominous features of our world

of appearances. But precisely because the yoni

thrusts the ordinary human into the realm of suffering and illusion it has

— as we shall see — become a “threshold to enlightenment” (Shaw, 1994, p. 59) for the tantric. Healed by the

mystic sexual act, it is also accorded a

higher, transcendental procreative

function. From it emerges the powerful host of

Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. We read in the relevant

texts “that the Buddha resides in the womb of the goddess and the

way of enlightenment [is experienced] as a pregnancy” (Faure, 1994, p.

189).

This central worship of the

yoni has led to a situation in which nearly all tantra

texts begin with the fundamental sentence, “I have heard it so: once

upon a time the Highest Lord lingered in the vaginas of the diamond women,

which represent the body, the language and the consciousness of all Buddhas”. Just as the opening

letters of the Bible are believed in a tenet of the Hebraic Kabbala to contain the concentrated essence of the

entire Holy Book, so too the first four letters of this tantric

introductory sentence — evam (‘I

have heard it so’) — encapsulate the entire secret

of the Diamond Path. “It has often been said that he who has understood evam has understood everything” (Banerjee, 1959, p. 7).

The word (evam) is already to be found in the early Gupta

scriptures (c. 300 C.E.) and

is represented there in the form of a hexagram, i.e., the symbol of mystic

sexual love. The syllable e

stands for the downward-pointing triangle, the syllable

vam is

portrayed as a upright triangle. Thus e

represents the yoni (vagina)

and vam

the lingam (phallus). E is the lotus, the source, the

location of all the secrets which the holy doctrine of the tantras teaches; the citadel of happiness, the throne,

the Mother. E further stands for

“emptiness and wisdom”. Masculine vam on the other hand lays claims to reverence as “vajra,

diamond, master of joys, method, great compassion, as the Father”. E and vam together form “the seal

of the doctrine, the fruit, the world of appearances, the way to

perfection, father (yab)

and mother (yum)” (see, among

others, Farrow and Menon, 1992, pp. xii ff.). The

syllables e-vam

are considered so powerful that the divine couple

can summon the entire host of male and female Buddhas

with them.

The origin of the gods and

goddesses

From the primordial tantric couple emanate pairs

of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, gods and demons.

Before all come the five male and five female Tathagatas (Buddhas of meditation), the five Herukas (wrathful Buddhas) in union with their partners, the eight Bodhisattvas with their consorts. We

also meet gods of time who symbolize the years, months and days, and the

“seven shining planetary couples”. The five elements (space, air, fire,

water and earth) are represented in pairs in divine form — these too find

their origin in mystic sexual love. As it says in the Hevajra Tantra: “By uniting the male and

female sexual organs the holder of the Vow performs the erotic union. From

contact in the erotic union, as the quality of hardness, Earth arises;

Water arises from the fluidity of semen; Fire arises from the friction of

pounding; Air is famed to be the movement and the Space is the erotic

pleasure” (Farrow and Menon, 1992, p. 134).

It is not just the “pure” elements which come from

the erotic communion, so do mixtures of them. Through the continuous union

of the masculine with the feminine the procreative powers flow into the

world from all of their body parts. In a commentary by the famous Tibetan scholar

Tsongkhapa, we read how the legendary Mount Meru, the continents, mountain ranges and all earthly

landscapes emerge from the essence of the hairs of the head, the bones,

gall bladder, liver, body hair, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, tendons, ribs,

excrement, filth (!), and pus (!). The springs, waterfalls, ponds, rivers

and oceans form themselves out of the tears, blood, menses, seed, lymph

fluid and urine. The inner fire centers of the head, heart, navel, abdomen

and limbs correspond in the external world to fire which is sparked by

striking stones or using a lens, a fireplace or a forest fire. Likewise all

external wind phenomena echo the breath which moves through the bodies of

the primeval couple (Wayman, 1977, pp. 234, 236).

In the same manner, the five “aggregate states”

(consciousness, intellect, emotions, perception, bodiliness)

originate in the primordial couple. The “twelve senses” (sense of hearing,

other phenomena, sense of smell, tangible things, sense of sight, taste,

sense of taste, sense of shape, sense of touch, smells, sense of spirit,

sounds) are also emanations of mystic sexual love. Further, each of the

twelve “abilities to act” is assigned to a goddess or a god — (the ability

to urinate, ejaculation, oral ability, defecation, control of the arm,

walking, leg control, taking, the ability to defecate, speaking, the

“highest ability” (?), urination).

Alongside the gods of the “domain of the body” we

find those of the “domain of speech”. The divine couple count as the origin

of language. All the vowels (ali) are assigned to the goddess; the god is the father

of the consonants (kali). When ali and kali (which can also appear as

personified divinities) unite, the syllables are formed. Hidden within

these as if in a magic egg are the verbal seeds (bija) from which the

linguistic universe grows. The syllables join with one another to build

sound units (mantras). Both often

have no literal meaning, but are very rich in emotional, erotic, magical

and mystical intentions. Even if there are many similarities between them,

the divine language of the tantras is still held

to be more powerful than the poetry of the West, as gods can be commanded

through the ritual singing of the germinal syllables. In Vajrayana

each god and every divine event obeys a specific mantra.

As erotic love leaves nothing aside, the entire

spectrum of the gods’ emotions (as long as these belong to the domain of

desire) is to originally be found in the mystical relationship of the

sexes. There is no emotion, no mood which does not originate here. The

texts speak of “erotic, wonderful, humorous, compassionate, tranquil,

heroic, disgusting, furious” feelings (Wayman,

1977, p. 328).

The origin of time and

emptiness

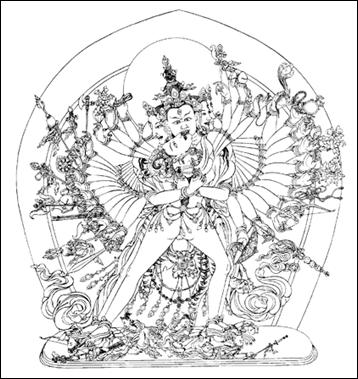

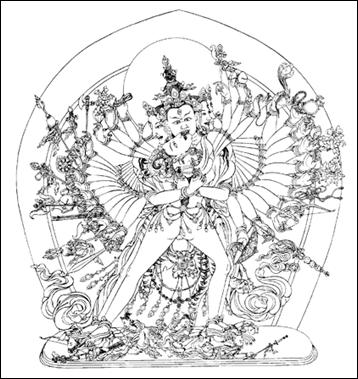

In the Kalachakra Tantra (“Time Tantra”)

the masculine pole is the time god Kalachakra, the feminine the time goddess Vishvamata. The chief symbols of the masculine

divinity are the diamond scepter (vajra) and the lingam

(phallus). The goddess holds a lotus blossom or a bell, both symbols of the

yoni (vagina). He rules as “Lord

of the Day”, she as “Queen of the Night”.

The mystery of time reveals itself in the love of

this divine couple. All temporal expressions of the universe are included

in the “Wheel of Time” (kala means ‘time’ and chakra ‘wheel’). When the time goddess Vishvamata and the time god Kalachakra

unite, they experience their communion as “elevated time”, as a “mystical

marriage”, as Hieros Gamos.

The circle or wheel (chakra)

indicates “cyclical time” and the law of “eternal recurrence”. The four

great epochs of the world (mahakalpa) are also hidden within the mystery of the

tantric primal couple, as are the many chronological modalities. The texts

describe the shortest unit of time as one sixty-fourth of a finger snap.

Seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months and years, the entire complex

tantric calendrical calculations, all emerge from

the mystic sexual love between Kalachakra and Vishvamata. The four heads of the time god correspond to

the four seasons. Including the “third eye”, his total of 12 eyes may be

apportioned to the 12 months of the year. Counting three joints per finger,

in Kalachakra’s

24 arms there are 360 bones, which correspond to the 360 days of the year

in the Tibetan calendar.

Kalachakra and Vishvamata

Time manifests itself as motion, eternity as

standstill. These two elements are also addressed in the Kalachakra Tantra.

Neither cyclical nor chronological time have any influence upon the state

of motionlessness during the Hieros Gamos. The river of time now runs dry, and the

fruit of eternity can be enjoyed. Such an experience frees the divine couple from both past and future, which prove to be

illusory, and gives them the timeless present.

What is the situation with the paired opposites of

space and time? In European philosophy and theoretical physics, this

relationship has given rise to countless discussions. Speculation about the

space-time phenomenon are, however, far less popular in Tantrism.

The texts prefer the term shunyata (emptiness) when speaking of “space”, and point

out the secret properties of “emptiness”, especially its paradoxical power

to bring forth all things. Space is emptiness, “but space, as understood in

Buddhist meditation, is not passive (in the western sense). ... Space is

the absolutely indispensable vibrant matrix for everything that is” (Gross,

1993, p. 203).

We can see shunyata (emptiness) as the most central term of the

entire Buddhist philosophy. It is the second ventricle of Mahayana Buddhism. (The first is karuna,

compassion for all living beings.) “Absolute emptiness” dissolves into

nothingness all the phenomena of being up to and including the sphere of

the Highest Self. We are unable to talk about emptiness, since the reality

of shunyata

is independent of any conceptual construction. It transcends thought and we

are not even able to claim that the phenomenal world does not exist. This radical negativism

has rightly been described as the “doctrine of the emptiness of emptiness”.

In the light of this fundamental inexpressibility

and featurelessness of shunyata, one

is left wondering why it is unfailingly regarded as a “feminine” principle

in Vajrayana

Buddhism. But it is! As its masculine polar opposite the tantras nominate consciousness (citta) or compassion (karuna). “The

Mind is the Lord and the Vacuity is the Lady; they should always be kept

united in Sahaja [the highest state of

enlightenment]”, as one text proclaims (Dasgupta,

1974, p. 101). Time and emptiness also complement one another in a polar

manner.

Thus, the Kalachakra divinity (the time god) cries emphatically

that, “through the power of time air, fire, water, earth, islands, hills,

oceans, constellations, moon, sun, stars, planets, the wise, gods,

ghosts/spirits, nagas (snake demons), the fourfold animal

origin, humans and infernal beings have been created in the emptiness” (Banerjee, 1959, p. 16). Once she has been impregnated

by “masculine” time, the “feminine” emptiness gives birth to everything.

The observation that the vagina is empty before it emits life is likely to

have played a role in the development of this concept. For this reason, shunyata may

never be understood as pure negativity in Tantrism,

but rather counts as the “shapeless” origin of all being.

The clear light

The ultimate goal of all mystic doctrines in the

widest variety of cultures is the ability to experience the highest clear

light. Light phenomena play such a significant role in Tantric Buddhism

that the Italian Tibetologist, Giuseppe Tucci, speaks of a downright “photism”

(doctrine of light). Light, from which everything stems, is considered the

“symbol of the highest intrinsicness” (Brauen, 1992, p. 65).

In describing supernatural light phenomena, the

tantric texts in no sense limit themselves to tracing these back to a mystical

primal light, but rather have assembled a complete catalog of “photisms” which maybe experienced. These include

sparks, lamps, candles, balls of light, rainbows, pillars

of fire, heavenly lights, and so forth which flash up during meditation.

Each of these appearances presages a particular level of consciousness,

ranked hierarchically. Thus one must traverse various light stages in order

to finally bathe in the “highest clear light”.

The truly unique feature of Tantrism

is that this “highest clear light” streams out of the yuganaddha, the Hieros Gamos. It

is in this sense that we must understand the following poetic sentence from

the Kalachakra Tantra:

“In a world purged of darkness, at the end of darkness awaits a couple” (Banerjee, 1959, p. 24).

Summarizing, we can say that Tantrism

has made erotic love between the sexes its central religious theme. When

the divine couple unite in bliss, then “by the force of their joy the

members of the retinue also fuse”, i.e., the other gods and goddesses, the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas with their wisdom consorts (Wayman, 1968, p. 291). The divine couple is

all-knowing, as it knows and indeed itself

represents the germinal syllables which produce the cosmos. With their

breath the time god (Kalachakra)

and time goddess (Vishvamata)

control the motions of the heavens. Astronomy along with every other

science has its origin in them. They are initiated into every level of

meditation, have mastery over the secret doctrines and every form of subtle

yoga. The clear light shines out of them. They know the laws of karma and

how they may be suspended. Compassionately, the god and goddess care for

humankind as if we were their children and devote themselves to the

concerns of the world. As master and mistress of all forms of time they

determine the rhythm of history. Being and not-being fuse within them. In

brief, the creative polarity of the divine couple produces the universe.

Yet this image of complete beauty between the

sexes does not stand on the highest altar of Tantric Buddhism. But what

could be higher than the polar principle of the universe and infinity?

Wisdom (prajna) and method (upaya)

Before answering this, we want to quickly view a

further pair of opposites which are married in yuganaddha. Up to now we have

not yet considered the most often cited polarity in the tantras,

“wisdom” (prajna)

and “method” (upaya).

There is no original tantric text, no Indian or Tibetan commentary and no

Western interpreter of Tantrism which does not

treat the “union of upaya

and prajna”

in depth.

“Wisdom” and “method” are held to be the outright

mother and father of all other tantric opposites. Every polar constellation

is derived from these two terms. To summarize, upaya stands for the

masculine principle, the phallus, motion, activity, the god, enlightenment,

and so forth; prajna

represents the feminine principle, the vagina, calm, passivity, the

goddess, the cosmic law. All women naturally count as prajna, all men as upaya. “The

commingling of this Prajna and Upaya [are] like the mixture of water and milk in a

state of non-duality” (Dasgupta, 1974, p. 93).

There is also the stated view that upaya becomes a fetter when it is not joined with prajna; only both together grant

deliverance and Buddhahood (Bharati,

1977, p. 171).

Prajna and Upaya

This almost limitless extension of the two

principles has led to a situation in which they are only rarely critically

examined. Do they stand in a truly polar

relation to one another? Why — we ask — does “wisdom” need “method”?

Somehow this pair of opposites do not fit together

— can there even be an unmethodical, chaotic “wisdom”? Isn’t prajna

(wisdom) enough on its own; does it not include “method” as a partial

aspect of itself? What is an “unmethodical” wisdom? Even if we translate upaya — as is

often done — as ‘technique’, we still do not have a convincing polar

correspondence to prajna.

This combination also seems far-fetched — why should “technique” and

“wisdom” meet in a mystic wedding? The opposition becomes even more absurd

and profane if we translate upaya (as it is clearly intended) as “cunning means” or

even “trick” or “ruse” (Wilber, 1987, p. 310). [2]

Whereas with “wisdom” one has some idea of what is meant, comprehending the

technoid term upaya presents major

difficulties. We must thus examine it in more detail.

“At all events”, writes David Snellgrove,

a renowned expert on Tantrism, “it must be

emphasized that here Means remains a doctrinal concept, serving as means to

an end, and in no sense can this concept be construed as an end in itself,

as is certainly the case with perfection of wisdom [prajna]” (Snellgrove,

1987, vol. 1, p. 283). “Method” is thus an instrument which is to be

combined with a content, “wisdom”. “Wisdom”, Snellgrove adds, “can be seen as representing the

evolving universe” (Snellgrove, 1987, vol. 1, p.

244). Due to the distribution of both principles along gender lines this

has a feminine quality.

The instrumental “method”, which is assigned to

the masculine sphere, thus proves itself — as we shall explain in more

detail — to be a sacred technique for controlling the feminine “wisdom”. Upaya is

nothing more than an instrument of manipulation, without any unique content

or substance of its own. Method is at best the means to an end (i.e.,

wisdom). Analytical reserve and technical precision are two of its

fundamental properties. Since wisdom — as we can infer from the quotation

from Snellgrove — represents the entire universe,

upaya

is the method with which the universe can be manipulated; and since prajna

represents the feminine principle and upaya the masculine, their

union implies a manipulation of the feminine by the masculine.

To illustrate this process, we should take a quick

look at a Greek myth which recounts how Zeus

acquired wisdom (Metis).

One day the father of the gods swallowed the female Titan Metis. (In Greek, metis means “wisdom”.) “Wisdom”

survived in his belly and gave him advice from there. According to this

story then, Zeus’s sole

contribution toward the development of “his” wisdom was a cunning swallow.

With this coarse but effective method (upaya) he could now present

himself as the fount of all wisdom. He even became, through the birth of Athena, the masculine “bearer” of

feminine prajna.

Metis,

the mother of Athena, actually gives birth to her

daughter in the stomach of the father of the gods, but it is he who brings

her willy-nilly into the world. In full armor, Athene, herself a symbol of

wisdom, bursts from the top of Zeus’s

skull. She is the “head birth” of her father, the product of his ideas.

Here, the swallowing of the feminine and its

imaginary (re)production (head birth) are the two techniques (upaya) with

which Zeus manipulates wisdom (prajna, Metis, Athene) to his own

ends. We shall later see how vividly this myth illustrates the process of

the tantric mystery.

At any rate, we would like to hypothesize that the

relation between the two tantric principles of “wisdom” and “method” is

neither one of complementarity, nor polarity, nor

even antinomy, but rather one of androcentric

hegemony. The translation of upaya as ‘trick’ is thoroughly justified. We can thus in

no sense speak of a “mystic marriage” of prajna and upaya, and unfortunately we must soon

demonstrate that very little of the widely distributed (in the West) conception

of Tantrism as a sublime art of love and a

spiritual refinement of the partnership remains.

The worship of “wisdom” (prajna) as a

embracing cosmic energy already had a significant role to play in Mahayana Buddhism. There we find an

extensive literature devoted to it, the Prajnaparamita texts, and it

is still cultivated throughout all of Asia.

In the famous Sutra of Perfected

Wisdom in Eight Thousand Verses (c. 100 B.C.E.)

for example, the glorification of prajnaparamita (“highest transcendental wisdom”) and the

description of the Bodhisattva way are central. “If

a Bodhisattva wishes to become a Buddha, […] he must always be energetic

and always pay respect to the Perfection of Wisdom [prajnaparamita]”, we read

there (D. Paul, 1985, p. 135). There are also instances in Mahayana

iconography where the “highest wisdom” is depicted in the form of a

female being, but nowhere here is there talk of manipulation or control of

the “goddess”. Devotion, fervent prayer, hymn, liturgical song, ecstatic

excitement, overflowing emotion and joy are the forms of expression with

which the believer worships prajnaparamita.

The guru as manipulator of the divine

In view of the previously suggested dissonance

between prajna

and upaya, we must ask ourselves who this

authority is, who via the “method” makes use of the wisdom-energy for his

own purposes. This question is all the more pertinent, since in the visible

reality of the tantric religions — in the culture of Tibetan Lamaism for

instance — Vajrayana

is never represented as a pair of equals, but almost exclusively as single

men, in very rare cases as single women. The two partners meet only to

perform the ritual sexual act and then separate.

It follows conclusively from what has already been

described that it must be the masculine principle which effects the

manipulation of the feminine wisdom. It appears in the figure of the

“tantric master”. His knowledge of the sacred techniques makes him a

“yogi”. Whenever he assumes the role of teacher he is known as a guru (Sanskrit) or a lama (Tibetan).

How does the tantric master’s exceptional position

of power arise? Every Vajrayana follower practices the so-called “Deity yoga”,

in which the self is imagined as a divinity. The believer distinguishes between

two levels. Firstly he meditates upon the “emptiness” of all being, in

order to overcome his bodily, mental, and spiritual impurities and “blocks”

and create an empty space. The core of this meditative process of

dissolution is the surrender of the individual ego. Following this, the

living image (yiddam)

of the particular divine being who should appear

in the appropriate ritual is formed in the yogi’s imaginative

consciousness. His or her body, color, posture, clothing, facial expression

and moods are described in detail in the holy texts and must be recreated

exactly in the mind. We are thus not dealing with an exercise of

spontaneous and creative free imagination, but rather with an accurate

reproduction of a codified archetype.

The practitioner may externalize or project the yiddam, so

that it appears before him. But this is just the first step; in those which

following he imagines himself as the deity. Thus he swaps his own personal

ego with that of a supernatural being. The yogi has now surmounted his

human existence and constitutes “to the very last atom” a unity with the

god (Glasenapp, 1940, p. 101).

But he must never lose sight of the fact that the

deity he has imagined possesses no autonomous existence. It exists purely

and exclusively as an emanation of his imagination and can thus be created,

maintained and destroyed at will. But who actually is this tantric master,

this manipulator of the divine? His consciousness has nothing in common

with that of a ordinary person, it must belong to

a sphere higher than that of the gods. The texts and commentaries describe

this “highest authority” as the “higher self” or as the primeval Buddha

(ADI BUDDHA), as the primordial one, the origin of all being, with whom the

yogi identifies himself.

Thus, when we speak of a “guru” in Vajrayana,

then according to the doctrine we are no longer dealing with an individual,

but with an archetypal and transcendental being, who has as it were

borrowed a human body in order to appear in the world. Events are not in the

control of the person (from the Latin persona

‘mask’), but rather the god acting through him. This in turn is the

emanation of an arch-god, an epiphany of the most high

ADI BUDDHA. Followed to its logical conclusion this means that the

Fourteenth Dalai Lama (the most senior tantric master of Tibetan Buddhism)

determines the politics of the Tibetans in exile not as a person, but as

the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara,

whose emanation he is. Thus, if we wish to pass judgment on his politics,

we must come to terms with the motives and visions of Avalokiteshvara.

The tantric master’s enormous power does not have

its origin in a Vajrayana

doctrine, but in the two main philosophical directions of Mahayana Buddhism (Madhyamika

and Yogachara).

The Madhyamika

school of Nagarjuna

(fifth century C.E.) discusses the principle of emptiness (shunyata)

which forms a basis for all being. Radically, this also applies to the

gods. They are purely illusory and for a yogi are worth neither more nor

less than a tool which he employs in setting his goals and then puts aside.

Paradoxically, this radical Buddhist perceptual

theory led to the admission of an immense multitude of gods, most of whom stemmed from the Hindu cultural sphere. From now on

these could populate the Buddhist heaven, something which was taboo in Hinayana. As they were in the final instance

illusory, there was no longer any need to fear them or regard them as

competition; since they could be “negated”, they could be “integrated”.

For the Yogachara school (fourth century C.E.), everything — the

self, the world and the gods — consists of “consciousness” or “pure

spirit”. This extreme idealism also makes it possible for the yogi to

manipulate the universe according to his wishes and plans. Because the

heavens and their inhabitants are nothing more than play figures of his

spirit, they can be produced, destroyed and exchanged at whim.

But what, in an assessment of the Vajrayana

system, should give grounds for reflection is the fact, already mentioned,

that the Buddhist pantheon presented on the tantric stage is codified in

great detail. Neither in the choreography nor the costumes have there been

any essential changes since the twelfth century C.E., if one is prepared to

overlook the inclusion of several minor protective spirits, of which the

youngest (Dorje Shugden

for example) date from the seventeenth century. In current “Deity yoga”,

practiced by an adept today (even one from the West), a preordained heaven

with its old gods is conjured up. The adept calls upon primeval images

which were developed in Indian/Tibetan, perhaps even Mongolian, cultural

circles, and which of course — as we will demonstrate in detail in the

second part of our study — represent the interests and political desires of

these cultures. [3]

Since the Master resides on a level higher than

that of a god, and is, in the final instance, the ADI BUDDHA, his pupils

are obliged to worship him as an omnipotent super-being, who commands the

gods and goddesses, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas. The

following apotheosis of a tantric teacher, which the semi-mythical founder

of Buddhism in Tibet,

Padmasambhava, laid down for an initiand, is symptomatic of countless similar prayers

in the liturgy of Tantrism: “You should know that

one’s master is more important than even the thousand buddhas

of this aeon. Why is that? It is because all the buddhas of this aeon appeared

after having followed a master. ... The master is the buddha

[enlightenment], the master is the dharma [cosmic law], in the same way the

master is also the sangha [monastic order]”

(Binder-Schmidt, 1994, p. 35). In the Guhyasamaja Tantra we

can read how all enlightened beings bow down before the teacher: “All the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas throughout the past, present

and future worship the Teacher .... [and] make

this pronouncing of vajra

words: ‘He is the father of all us Buddhas, the

mother of all us Buddhas, in that he is the

teacher of all us Buddhas’” (Snellgrove,

1987, vol. 1, p. 177).

A bizarre anecdote from the early stages of Tantrism makes this deification of the gurus even more

apparent. One day, the famous vajra master, Naropa, asked

his pupil, Marpa, “If I and the god Hevajra appeared before you at the same

time, before whom would you kneel first?”. Marpa thought, “I see my guru every day, but if Hevajra

reveals himself to me then that is indeed a quite extraordinary event, and

it would certainly be better to show respect to him first!”. When he told

his master this, Naropa clicked two fingers and

in that moment Hevajra appeared with his entire retinue.

But before Marpa could prostrate himself in the

dust before the apparition, with a second click of the fingers it vanished

into Naropa’s heart. “You made a mistake!” cried

the master (Dhargyey, 1985, p. 123).

In another story, the protagonists are this same Naropa and his instructor, the Kalachakra Master Tilopa. Tilopa spoke to his

pupil, saying, “If you want teaching, then construct a mandala!”. Naropa was unable to find

any seeds, so he made the mandala out of sand.

But he sought without success for water to cement the sand. Tilopa asked him, “Do you have blood?” Naropa slit his veins and the blood flowed out. But

then, despite searching everywhere, he could find no flowers. “Do you not

have limbs?” asked Tilopa. “Cut off your head and

place it in the center of the mandala. Take your

arms and legs and arrange them around it!” Naropa

did so and dedicated the mandala to his guru, then he collapsed from blood loss. When he regained

consciousness, Tilopa asked him, “Are you

content?” and Naropa answered, “It is the

greatest happiness to be able to dedicate this mandala,

made of my own flesh and blood, to my guru”.

The power of the gurus — this is what these

stories should teach us — is boundless, whilst the god is, finally, just an

illusion which the guru can produce and dismiss at will. He is the

arch-lord, who reigns over life and death, heaven and hell. Through him

speaks the ABSOLUTE SPIRIT, which tolerates nothing aside from itself.

The pupil must completely surrender his individual

ego and transform it into a subject of the SPIRIT which dwells in his

teacher. “I and my teacher are one” means then, that

the same SPIRIT lives in both.

The appropriation of gynergy and androcentric power strategies

Only in extremely rare cases is

the omnipotence and divinity of a yogi acquired at birth. It is usually the

result of a graded and complicated spiritual progression. Clearly, to be

able to realize his omnipotence, which should transcend even the sexual

polarity of all which exists, a male tantric master requires a substance,

which we term “gynergy” (female energy), and which we intend to examine in more detail in the

following. As he cannot, at the outset of his path to power, find this

“elixir” within himself, he must seek it there where in accordance with the

laws of nature it may be found in abundance, in women.

Vajrayana is therefore — according to the

assessments of no small number of Western researchers of both sexes — a

male sexual magic technique designed to “rob” women of their particularly

female form of energy and to render it useful for the man. Following the

“theft”, it flows for the tantric adept as the spring which powers his

experiences of spiritual enlightenment. All the potencies which, from a

Tibetan point of view, are to be sought and found in the feminine sphere

are truly astonishing: knowledge, matter, sensuality, language,

light — indeed, according to the tantric texts, the yogi perceives

the whole universe as feminine. For him, the feminine force (shakti) and

feminine wisdom (prajna)

constantly give birth to reality; even transcendental truths such as

“emptiness” (shunyata)

are feminine. Without “gynergy”, in the tantric view of things none of the

higher levels along the path to enlightenment can be reached, and hence in no

circumstances a state of perfection.

In order to be able to acquire the primeval

feminine force of the universe, a yogi must have mastered the appropriate

spiritual methods (upaya),

which we examine in detail later in this study. The well-known investigator

of Tibetan culture, David Snellgrove, describes

their chief function as the transmutation of the feminine form into the

masculine with the intention of accumulating power. It is for this and no

other reason that the tantric seeks contact with a female. Usually, “power

flows from the woman to the man, especially when she is more powerful than

he”, the Indologist Doniger

O’Flaherty (O’Flaherty, 1982, p. 263) informs us. Hence, since the powerful

feminine creates the world, the “uncreative” masculine yogi can only become

a creator if he appropriates the creative powers of the goddess. “May I be

born from birth to birth”, he thus cries in the Hevajra Tantra, “concentrating in myself the

essence of woman” (Snellgrove, 1959, p. 116). He

is the sorcerer who believes that all power is feminine, and that he knows

the secret of how to manipulate it.

The key to his

dreams of omnipotence lies in how he is able to transform himself into a

“supernatural” being, an androgyne who has access to the

potentials of both sexes. The two sexual energies now lose their equality

and are brought into a hierarchical relation with each other in which the

masculine part exercises absolute control over the feminine.

When, in the reverse situation, the feminine

principle appropriates the masculine and attempts to dominate it, we have a

case of gynandry.

Gynandric rites are known from the Hindu tantras. But in contrast, in androcentric

Buddhism we are dealing exclusively with the production of a “perfect”

androgynous state, i.e., in social terms with the power of men over women

or, in brief, the establishment of a patriarchal monastic regime.

Since the “bisexuality” of

the yogi represents a precondition for the development of his power, it

forms a central topic of discussion in every highest tantra.

It is known simply as the “two-in-one” principle, which suspends all

oppositions, such as wisdom and method, subject and object, emptiness and

compassion, but above all masculine and feminine (Snellgrove,

1987, vol. 1, p. 285). Other phrases include “bipolarity” or the

realization of “bisexual divinity within one’s own body” (Herrmann-Pfand, 1992, p. 314).

However, the “two-in-one” principle is not

directed at a state beyond sexuality and erotic love, as modern

interpreters often misunderstand it to be. The tantric master deliberately

utilizes the masculine/feminine sexual energies to obtain and exercise

power and does not destroy them, even if they are only present within his

own identity after the initiation. They continue to function there as the

two polar primeval forces, but now within the androgynous yogi.

Thus, in Tantrism we are

in any case dealing with an erotic cult, one which recognizes cosmic erotic

love as the defining force of the universe, even if it is manipulated in

the interests of power. This is in stark contrast to the asexual concepts

of Mahayana Buddhism. “The state

of bisexuality, defined as the possession of both masculine and feminine

sexual powers, was considered unfortunate, that is, not conducive to

spiritual growth. Because of the excessive sexual power of both masculinity

and femininity, the bisexual individual had weakness of will or inattention

to moral precepts”, reports Diana Paul in reference to the “Great Vehicle”

(D. Paul, 1985, pp. 172–173).

But Vajrayana does not let itself be intimidated by such

proclamations, but instead worships the androgyne

as a radiant diamond being, who feels in his heart “the blissful kiss of

the inner male and female forces” (Mullin, 1991, p. 243). The tantric androgyne is supposed to actually partake of the lusts

and joys of both sexes, but just as much of their concentrated power.

Although in his earthly form he appears before us as a man, the yogi

nonetheless rules as both man and

woman, as god and goddess, as

father and mother at once. The initiand is instructed to “visualize the lama as Kalachakra in

Father and Mother aspect, that is to say, in union with his consort” (Dalai

Lama XIV, 1985, p. 174), and must then declare to

his guru, “You are the mother, you are the father, you are the teacher of

the world!”(Grünwedel, Kalacakra II, p. 180).

The vaginal Buddha

The goal of androgyny is the acquisition of

absolute power, as, according to tantric doctrine, the entire cosmos must

be seen as the play and product of both sexes. Now united in the mystic

body of the yogi, the latter thereby believes he has the secret birth-force

at his disposal — that natural ability of woman which he as man principally

lacks and which he therefore desires so strongly.

This desire finds expression in, among

other things, the royal title Bhagavan (ruler or regent), which he acquires after the

tantric initiation. The Sanskrit word bhaga originally designated the female

pudendum, womb, vagina or vulva. But bhaga also means happiness, bliss, wealth, sometimes emptiness. This

metaphor indicates that the multiplicity of the world emerges from the womb

of woman. The yogi thus lets himself be revered

in the Kalachakra Tantra as

Bhagavat

or Bhagavan,

as a bearer of the female birth-force or alternatively as a “bringer of

happiness”. “The Buddha is called Bhagavat, because he possesses the Bhaga, this characterizes the quality of his rule” (Naropa, 1994, p. 136), we can read in Naropa’s commentary from the eleventh century, and the

famous tantric continues, “The Bhaga is according to tradition the horn of plenty in

possession of the six boons in their

perfected form: sovereignty, beauty, good name/reputation, abundance,

insight, and the appropriate force to be able to achieve the goals set” (Naropa, 1994, p. 136). In their introduction to the Hevajra Tantra

the contemporary authors, G. W. Farrow and I. Menon,

write, “In the tantric view the Bhagavan is

defined as the one who possesses Bhaga, the womb,

which is the source” (Farrow and Menon, 1992, p.

xxiii).

Although this male usurpation of the Bhaga first

reaches its full extent and depth of symbolism in Tantrism,

it is presaged by a peculiar bodily motif from an earlier phase of

Buddhism. In accordance with a broadly accepted canon, an historical Buddha

must identify himself through 32 distinguishing features. These take the

form of unusual markings on his physical body, like, for example, sun-wheel

images on the soles of his feet. The tenth sign, known to Western medicine

as cryptorchidism,

is that the penis is covered by a thick fold of skin, “the concealment of

the lower organs in a sheath”; this text goes on to add, “Buddha’s private

parts are hidden like those of a horse [i.e., stallion]” (Gross, 1993, p.

62).

Even if cryptorchidism

as an indicator of the Enlightened One in Mahayana Buddhism is meant to show his “asexuality”, in our

opinion in Vajrayana

it can only signal the appropriation of feminine sexual energies without

the Buddha thus needing to renounce his masculine potency. Instead, in

drawing the comparison to a stallion which has a penis which naturally

rests in a “sheath”, it is possible to tap into one of the most powerful

mythical sexual metaphors of the Indian cultural region. Since the Vedas the stallion has been seen as

the supreme animal symbol for male potency. In Tibetan folklore, the Dalai

Lamas also possess the ability to “retract” their sexual organs (Stevens,

1993, p. 180).

The Buddha as mother and

the yogi as goddess

The “ability to give birth” acquired through the

“theft” of gynergy transforms the guru into a

“mother”, a super-mother who can herself produce gods. Every Tibetan lama

thus values highly the fact that he can lay claim to the powerful symbols

of motherhood, and a popular epithet for tantric yogis is “Mother of all Buddhas” (Gross, 1993, p. 232). The maternal role

logically presupposes a symbolic pregnancy. Consequently, being “pregnant”

is a common metaphor used to describe a tantric master’s productive

capability (Wayman, 1977, p. 57).

But despite all of his motherly qualities, in the

final instance the yogi represents the male arch-god, the ADI BUDDHA, who

produced the mother goddess out of himself as an archetype: “It is to be

noted that the primordial goddess had emanated from the Lord”, notes an

important tantra interpreter, “The Lord is the beginningless eternal One; while the Goddess, emanating

from the body of the Lord, is the produced one” (Dasgupta,

1946, p. 384). Eve was created from Adam’s rib, as Genesis already informs

us. Since, according to the tantric initiation, the feminine should only

exist as a manipulable element of the masculine,

the tantras talk of the “together born female” (Wayman, 1977, p. 291).

Once the emanation of the mother

goddess from the masculine god has been formally incorporated in the canon,

there is no further obstacle to a self-imagining and self-production of the

lama as goddess. “Then behold yourself as divine woman in empty form”

(Evans-Wentz, 1937, p. 177), instructs a guide to meditation for a pupil.

In another, the latter declaims, “I myself instantaneously become the Holy

Lady” (quoted by Beyer, 1978, p. 378).

Steven

Segal (Hollywood actor): The Dalai Lama “is the great mother of everything nuturing and loving. He accepts all who come without judgement.” (Schell, 2000, p. 69)

Once kitted out with the force of the feminine,

the tantric master even has the ability to produce whole hosts of female

figures out of himself or to fill the whole universe with a single female

figure: “To begin with, imagine the image (of the goddess Vajrayogini)

of roughly the size of your own body, then in that of a house, then a hill,

and finally in the scale of outer space” (Evans-Wentz, 1937, p. 136). Or he

imagines the cosmos as an endlessly huge palace of supernatural couples:

“All male divinities dance within me. And all female divinities channel

their sacred vajra

songs through me”, the Second Dalai Lama writes lyrically in a tantric song

(Mullin, 1991, p. 67). But “then, he [the yogi] can resolve these couples

in his meditation. Little by little he realizes that their objective

existence is illusory and that they are but a function. ... He transcends

them and comes to see them as images reflected in a mirror, as a mirage and

so on” (Carelli, 1941, p. 18).

However, outside of the rites and meditation

sessions, that is, in the real world, the double-gendered super-being

appears almost exclusively in the body of a man and only very rarely as a

woman, even if he exclaims in the Guhyasamaja Tantra, “I am without doubt any figure. I am woman

and I am man, I am the figure of the androgyne” (Gäng, 1998, p. 66).

What happens to the woman?

Once the yogi has “stolen” her gynergy using sexual magic techniques, the woman vanishes from the

tantric scenario. “The feminine partner”, writes David Snellgrove,

“known as the Wisdom-Maiden [prajna] and supposedly embodying this great perfection

of wisdom, is in effect used as a means to an end, which is experienced by

the yogi himself. Moreover, once he has mastered the requisite yoga

techniques he has no need of a feminine partner, for the whole process is

re-enacted within his own body. Thus despite the eulogies of women in these

tantras and her high symbolic status

, the whole theory and practice is given for the benefit of males” (Snellgrove, 1987, vol. 1, p. 287).

Equivalent quotations from many other Western

interpreters of Tantrism can be found: “In ... Tantrism ... woman is means, an alien object, without

possibility of mutuality or real communication” (quoted by Shaw, 1994, p.

7). The woman “is to be used as a ritual object and then cast aside” (also

quoted by Shaw, 1994, p. 7). Or, at another point: the yogis had “sex

without sensuality ... There is no relationship of intimacy with an

individual — the woman ... involved is an object, a representation of power

... women are merely spiritual batteries” (quoted by Shaw, 1994, n. 128,

pp. 254–255). The woman functions as a “salvation tool”, as an “aid on the

path to enlightenment”. The goal of Vajrayana is even “to destroy

the female” (quoted by Shaw, 1994, p. 7).

Incidentally, this functionalization

of the sexual partner is addressed — as we still have to show — without

deliberation or shame in the original Vajrayana texts. Modern

Western authors with views compatible to those of Buddhism, on the

contrary, tend toward the opinion that the tantric androgyne

harmonizes both sexual roles equally within itself, so that the androgynous

pattern is valid for both men and women. But this is not the case. Even at

an etymological level, androgyny (from Ancient Greek anér ‘man’ and gyné ‘woman’) cannot be applied to both sexes. The term

denotes — when taken literally — the male-feminine forces possessed by a

man, whilst for a woman the respective phenomenon would have to be termed “gynandry” (female-masculine forces possessed by a

woman).

Androgyny vs. gynandry

Since androgyny and gynandry

are used in reference to the organization of sex-specific energies and not

a description of physical sexual characteristics, it could be felt that we are

being overly pedantic here. That would be true if it were not that Tantrism involved an extreme cult of the male body,

psyche and spirit. With extremely few exceptions all Vajrayana gurus are men. What

is true of the world of appearances is also true at the highest

transcendental level. The ADI BUDDHA is primarily depicted in the form of a

man.

Following our discussion of the “mystic”

physiology of the yogi, we shall further be able to see that this describes

the construction of a masculine body of energy. But any doubts about

whether androgyny represents a virile usurpation of feminine energies ought

to vanish once we have aired the secrets of the tantric seed (semen)

gnosis. Here the male yogi uses a woman’s menstrual blood to construct his

bisexual body.

Consequently, the attempt to create an androgynous being out of a woman

means that her own feminine essence becomes subordinated to a masculine

principle (the principle of anér). Even when she exhibits the outward sexual

characteristics of a woman (breasts and vagina), she mutates, as we know

already from Mahayana Buddhism,

in terms of energy into a man. In contrast, a truly female counterpart to

an androgynous guru would be a gynandric

mistress. The question, however, is whether the techniques taught in the

Buddhist tantras are at all suitable for

instituting a process transforming a woman in the direction of gynandry, or whether they have been written by and for

men alone. Only after a detailed description of the tantric rituals will we

be able to answer this question.

The absolute power of the “Grand Sorcerer” (Maha Siddha)

The goal of tantric androgyny is the concentration

of absolute power in the tantric master, which in his view constitutes the

unrestricted control over both cosmic primal

forces, the god and the goddess. If one assumes that he has, through

constant meditative effort, destroyed his individual ego, then it is no

longer a person who has concentrated this power within himself. In place of

the human ego is the superego of a god with far-reaching powers. This

superhuman subject knows no bounds when it proclaims in the Hevajra Tantra,

“I am the revealer, I am the revealed doctrine and I am the disciple

endowed with good qualities. I am the goal, I am the master of the world

and I am the world as well as the worldly things” (Farrow and Menon, 1992, p. 167). In the tantras

there is a distinction between two types of power:

- Supernatural power, that is,

ultimately, enlightened consciousness and Buddhahood.

- Worldly power such as wealth,

health, regency, victory over an enemy, and so forth.

But a classification of the tantras

into a lower category, concerned with only worldly matters, and a higher,

in which the truly religious goals are taught, is

not possible. All of the writings concern both the “sacred” and the

“profane”.

Supernatural power gives the tantric master

control over the whole universe. He can dissolve it and re-establish it. It

grants him control over space and time in all of their forms of expression.

As “time god” (Kalachakra)

he becomes “lord of history”. As ADI BUDDHA he determines the course of

evolution.

Worldly power means, above all, being successfully

able to command others. In the universalism of Vajrayana those commanded are

not just people, but also beings from other transhuman

spheres — spirits, gods and demons. These can not

be ruled with the means of this world alone, but only through the art of

supernatural magic. Fundamentally, then, the power of a guru increases in

proportion to the number and effectiveness of his “magical forces” (siddhis).

Power and the knowledge of the magic arts are synonymous for a tantric

master.

Such a pervasive presence of magic is somewhat

fantastic for our Western consciousness. We must therefore try to transpose

ourselves back to ancient India,

the fairytale land of miracles and secrets and imagine the occult ambience

out of which Tantric Buddhism emerged. The Indologist

Heinrich Zimmer has sketched the atmosphere of this time as follows: “Here

magic is something very real. A magic word, correctly pronounced penetrates

the other person without resistance, transforms, bewitches

them. Then under the spell of involuntary participation the other is porous

to the fluid of the magic-making will, it electrically conducts the current

which connects with him” (Zimmer, 1973, p. 79). In the Tibet of

the past, things were no different until sometime this century. All the

phenomena of the world are magically interconnected, and “secret threads

[link] every word, every act, even every thought to the eternal grounding

of the world” (Zimmer, 1973, p. 18). As the “bearers of magical power” or

as “sorcerer kings” the tantric yogis cast out nets woven from such

threads. For this reason they are known as Maha Siddhas, “Grand Sorcerers”.

Lamaist “sorcerer” (a Ngak’phang gÇodpa)

When we pause to examine what the tantras say about the magical objects with which a Maha Siddha is

kitted out, we are reminded of the wondrous objects which only fairytale

heroes possess: a magical sword which brings victory and power over all

possible enemies; an eye ointment with which one can discover hidden

treasure; a pair of “seven-league boots” that allow the adept to reach any

place on earth in no time at all, traveling both on the ground and through

the air; there is an elixir which alchemically transforms base metals into

pure gold; a magic potion which grants eternal youth and a wonder cure to

protect from sickness and death; pills which give him the ability to assume

any shape or form; a magic hood that makes the sorcerer invisible. He can

assume the appearance of several different individuals at the same time, can suspend gravity and can read people’s

thoughts. He is aware of his earlier incarnations, has mastered all

meditation techniques; he can shrink to the size of an atom and expand his

body outward to the stars. He possesses the “divine eye” and “divine ear”.

In brief, he has the power to determine everything according to his will.

The Maha Siddhas control the universe through their spells,

enchantment formulas, or mantras. “I am aware”, David Snellgrove

comments, “that present-day western Buddhists, specifically those who are

followers of the Tibetan tradition, dislike this English word [spell,] used for mantra and the rest

because of its association with vulgar magic. One need only reply that

whether one likes it or not, the greater part of the tantras

are concerned precisely with vulgar magic, because this is what most people