|

© Victor & Victoria Trimondi

The Shadow of the Dalai Lama – Part

I – 4. The law of inversion

4. THE LAW OF INVERSION

Every type of passion (sexual pleasure, fits of

rage, hate and loathing) which is normally considered taboo by Buddhist ethical

standards, is activated and nurtured in Vajrayana with the goal of

then transforming it into its opposite. The Buddhist monks, who are usually

subject to a strict, puritanical-seeming set of rules, cultivate such

“breaches of taboo” without restriction, once they have decided to follow

the “Diamond Path”. Excesses and extravagances now count as part of their

chosen lifestyle. Such acts are not simply permitted, but are prescribed

outright, because according to tantric doctrine, evil can only be driven

out by evil, greed by greed alone, and poison is the only cure for poison.

Suitably radical instructions can be found in the Hevajra Tantra:

“A wise man ... should remove the filth of his mind by filth ... one must

rise by that through which one falls”, or, more vividly, “As flatulence is

cured by eating beans so that wind may expel wind, as a thorn in the foot can be

removed by another thorn, and as a poison can be neutralized by poison, so

sin can purge sin” (Walker, 1982, p. 34). For the same reason, the Kalachakra Tantra

exhorts its pupils to commit the following: to kill, to lie, to steal, to

break the marriage vows, to drink alcohol, to have sexual relations with

lower-class girls (Broido, 1988, p. 71). A

Tantric is freed from the chains of the wheel of life by precisely that

which imprisons a normal person.

As a tantric saying puts it, “What binds the fool,

liberates the wise” (Dasgupta, 1974, p. 187), and

another, more drastic passage emphasizes that, “the same deed for which a

normal mortal would burn for a hundred million eons, through this same act

an initiated yogi attains enlightenment” (Eliade,

1985, p. 272). According to this, every ritual is designed to catapult the initiand into a state beyond good and evil.

This spiritual necessity to encounter the

forbidden, has essentially been justified via five arguments:

Firstly, through breaking a taboo for which there

is often a high penalty, the adept confirms the core of the entire Buddhist

philosophy: the emptiness (shunyata) of all appearances. “I am void, the world is

void, all three worlds are void”, the Maha Siddha Tilopa

triumphantly proclaims — therefore “neither sin nor virtue” exist (Dasgupta, 1974, p. 186). The shunyata principle thus

provides a metaphysical legitimization for any conceivable “crime”, as it

actually lacks any inherent existence.

A second argument follows from the emptiness, the

“equivalence of all being”. Neither purity nor impurity, neither lust nor

loathing, neither beauty nor ugliness exist. There is thus “no difference

between food and offal, between fruit juice and blood, between vegetable

sap and urine, between syrup and semen” (Walker, 1982, p.32). A fearless maha siddha

justifies a serious misdeed of which he has been accused with the words: A fearless maha siddha

justifies a serious misdeed of which he has been accused with the words:

“Although medicine and poison create contrary effects, in their ultimate

essence they are one; likewise negative qualities and aids on the path, one

in essence, should not be differentiated” (quoted by Stevens, 1990, p. 69).

Thus the yogi could with a

clear conscience wander along ways on the far side of the dominant moral codex. “By the same evil acts that bring people into

hell the one who uses the right means gains salvation, there is no doubt.

All evil and virtue are said to have thought as their basis” (Snellgrove, 1987, vol. 1, p. 174).

The third — somewhat ad hoc, but nonetheless

frequent — justification for the “transgressions” of the Vajrayana

consists in the Bodhisattva vow of Mahayana

Buddhism, which requires that one aid and assist every creature until it

attains enlightenment. Amazingly, this pious purpose can render holy the

most evil means. “If”, we can read in one of the tantras,

“for the good of all living beings or on account of the Buddha’s teaching

one should slay living beings, one is untouched by sin. ... If for the good

of living beings or from attachment for the Buddha’s interest, one seizes

the wealth of others , one is not touched by sin”,

and so forth (Snellgrove, 1987, vol. 1, p. 176).

In the course of Tibetan history the Bodhisattva vow has, as we shall show

in the second part of our study, legitimated numerous political and

family-based murders, whereby the additional “clever” argument was also

employed, that one had “freed” the murder victim from the world of

appearances (samsara)

and that he or she thus owed a debt of thanks to the murderer.

The fourth argument, which was also widespread in

other magical cultures, is familiar to us from homeopathy, and states: similia similibus curantur (‘like cures like’). In this healing

practice one usually works with tiny quantities, major sins can thus be

expiated by more minor transgressions.

The fifth and final argument attempts to persuade

us that enlightenment per se arises

through the radical inversion of its opposite and that there is absolutely

no other possible way to break free of the chains of samsara. Here, the tantric

logic of inversion has become a dogma which no longer tolerates other paths

to enlightenment. In this light, we can read in the Guhyasamaja Tantra that

“the most lowly-born, flute-makers and so forth, such [people] who

constantly have murder alone in mind, attain perfection via this highest

way” (quoted by Gäng, 1988, p. 128). Yes, in some

texts an outright proportionality exists between the magnitude of the

“crime” and the speed with which the spiritual “liberation” occurs.

However, this tantric logic of inversion contains

a dangerous paradox. On the one hand, Vajrayana stands not just in

radical opposition to “social” norms, but likewise also to the original

fundamental rules of its own Buddhist system. Thus, it must constantly fear

accusations and persecution from its religious brethren. On the other there

is the danger mentioned by Friedrich Nietzsche, that anyone who too often

looks monsters in the face can themselves become a monster.

Sadly, history — especially that of Tibet — teaches us how many tantra masters were not able

to rid themselves of the demons that they summoned. We shall trace this

fate in the second part of our study.

The twilight language

In order to keep hidden from the public all the

offensive things which are implicated by the required breaches of taboo,

some tantra texts make use of a so-called

“twilight language” (samdhya-bhasa).

This has the function of veiling references to taboo substances, private

bodily parts, and illegal deeds in poetic words, so that they cannot be

recognized by the uninitiated. For example, one says “lotus” and means

“vagina”, or employs the term “enlightenment consciousness” (bodhicitta)

for sperm, or the word “sun” (surya) for menstrual blood. Such a list of synonyms can

be extended indefinitely.

It would, however, be hasty to presume that the

potential of the tantric twilight language is exhausted by the employment

of euphemistic expressions for sexual events in order to avoid stirring up

offense in the world at large. In keeping with the magical world view of Tantrism, an equivalence or interdependence is often

posited between the chosen “poetic” denotation and its counterpart in

“reality”. Thus, as we shall later see, the male seed does indeed effect enlightenment consciousness (bodhicitta) when it is

ritually consumed, and the vagina does in fact transform itself through

meditative imagination into a lotus.

Of course, in such a metaphoric twilight

everything is possible! Since, in contrast to the extensive commentaries,

the taboo violations are often explicitly and unashamedly discussed in the

original tantric texts, modern textual exegetes have often turned the

tables. For example, in the unsavory horror scenes which are recounted

here, the German lama Govinda sees warning signs

which act as a deterrent to impudent intruders into the mysteries. To

prevent unauthorized persons entering paradise, it is depicted as a

slaughterhouse. But this imputed circumscription of the beautiful with the

horrible contradicts the sense of the tantras,

the intention of which is precisely to be sought in the transformation of

the base into the sublime and thus the deliberate confrontation with the

abominations of this world.

The scenarios which are presented in the following

pages are indeed so abnormal that the hair of the early Western scholars

stood on end when they first translated the tantric texts from Tibetan or

Sanskrit. E. Burnouf was dismayed: “One hesitates

to reproduce such hateful and humiliating teachings”, he wrote in the year

1844 (von Glasenapp, 1940, p. 167). Almost a

century later, even world famous Tibetologists

like Giuseppe Tucci or David Snellgrove

admitted that they had simply omitted certain passages from their

translated versions because of the horrors described therein, even though

they thus abrogated their scholarly responsibilities (Walker, 1982, p.

121). Today, in the age of unlimited information, any resistance to the

display of formerly taboo pictures is rapidly evaporating. Thus, in some

modern translation one is openly confronted with all the “crimes and sexual

deviations” in the tantras.

Sexual desire

Let us begin anew with the topic of sex. This is

the axis around which all of Tantrism revolves.

We have already spoken at length about why women were regarded as the

greatest obstacle along the masculine path to enlightenment. Because the

woman represents the feared gateway to rebirth, because she produces the

world of illusion, because she steals the forces of the man — the origins

of evil lie within her. Accordingly, to touch a woman was also the most

serious breach of taboo for a Buddhist from the pre-tantric phase. The

severity of the transgression was multiplied if it came to sexual

intercourse.

But precisely because most extreme estrangement

from enlightenment is inherent to the “daughters of Mara”, because they are considered the greatest obstacle for a

man and barricade the realm of freedom, according to the tantric “law of

inversion” they are for any adept the most important touchstone on the

initiation path. He who understands how to gain mastery over women also understands

how to control all of creation, as it is represented by him. On account of

this paradox, sexual union enjoys absolute priority in Vajrayana. All other ritual

acts, no matter how bizarre they may appear, are derived from this sexual

magic origin.

Actually, the same tantric postulate — that the

overcoming of an opposite pole should be considered more valuable and

meritorious the more abnormal characteristics it exhibits — must also be

valid for sexuality:. According to the “law of inversion”, the more gloomy,

repulsive, aggressive and perverse a woman is, the more suitable she must

be to serve as a sexual partner in the rituals. But the preference of the

yogis for especially young and attractive girls (which we mention above)

seems to contradict this postulated ugliness.

Incidentally, the Kalachakra Tantra is

itself aware of this contradiction, but is unable to resolve it. Thus the

third book of the Time Tantra has the following

suggestions to make: “Terrible women, furious, stuck-up, money-hungry, quarrelsome...are

to be avoided” (Grünwedel, Kalacakra III, p. 121). But then, a few pages later, we find precisely

the opposite: “A woman, who has abandoned herself to a lust for life, who

takes delight in human blood ... is to be revered by the yogi” (Grünwedel, Kalacakra III,

p. 146). The fourth book deals with the “law of inversion” directly, and in

verse 207 describes the karma mudra as a “gnarled hetaera”. Directly after this

follows the argument as to why a goddess must be hiding behind the face of

the hetaera, since for the yogi, “gold [can] be worth the same as copper, a

jewel from the crown of a god the same as a sliver of glass, if unheard of

masculine force can be received through the loving donations of trained

hetaeras ...” (Grünwedel, Kalacakra IV, p. 209) — that is, the highest masculine can be won from

the basest feminine.

In this light, the Chakrasamvara Tantra

recommends erotic praxis with haughty, moody, proud, dominant, wild, and

untamable women, and the yogini Laksminkara urges the reader to revere a woman

who is “mutilated and misshapen” (Gäng, 1988, p.

59). The Maha Siddha Tilopa also adhered strictly to the tantric politics of

inversion and copulated with a woman, who bore the “eighteen marks of

ugliness”, whatever they may be. His pupil Naropa

followed in his footsteps and was initiated by an “ugly leprous old crone”.

The later’s successor, Marpa,

received his initiation at the hands of a “foul-smelling ‘funeral-place dakini’ ... with long emaciated breasts and huge sex

organs of offensive odor” (Walker, 1982, p. 75).

Whilst the ugly “love partners” threaten at the

outset the way to salvation and the life of an adept, at the end of the

tantric process of inversion they shine like fairy-tale beauties, who have been transformed from toads into princesses. Thus, after the

transmutation, a “jackal jaws” has become the “dakini

of wisdom”; a “lion’s gob” the honourable “Buddha dakini”

with “a bluish complexion and a radiant smile”; a “beak-face” a “jewel dakini” with an “pretty, white

face” and so forth (Stevens, 1990, p. 97). All these charming creatures are under the

complete control of their guru, who through the conquest of the demonic

woman has attained the qualification of sorcerer and now calls the tune for

the transformed demonesses.

For readily understandable reasons the fact

remains that in the sexual magic practices a preference is shown for

working with young and attractive girls. But even for this a paradoxical

explanation is offered: Due to their attractiveness the virgins are far

more dangerous for the yogi than an old hag. The chances that he lose his emotional and sexual self-control in such a

relationship are thus many times higher. This means that attractive women

present him with a even greater challenge than do

the ugly.

The tantras are more

consistent when applying the “law of inversion” to the social class of the

female partners than they are with regard to age and beauty. Women from

lower castes are not just recommendable, but rather appear to be downright

necessary for the performance of certain rituals. The Kalachakra Tantra

lists female gardeners, butchers, potters, whores, and needle-workers among

its recommendations (Grünwedel, Kalacakra III, pp. 130, 131). In other texts there

is talk of female pig-herds, actresses, dancers, singers, washerwomen,

barmaids, weavers and similar. “Courtesans are also favored”, writes the Tibet

researcher Matthias Hermanns, “since the more

lecherous, depraved, dirty, morally repugnant and dissolute they are, the

better suited they are to their role” (Hermanns,

1975, p. 191). This appraisal is in accord with the call of the Tantric Anangavajra to accept any mudra, whatever nature she may have, since “everything having its

existence in the ultimate non-dual substance, nothing can be harmful for

yoga; and therefore the yogin should enjoy

everything to his heart’s content without the least fear or hesitation” (Dasgupta, 1974, p. 184).

Time and again, so-called candalis are mentioned as the

Tantric’s sexual partners. These are girls from

the lowest caste, who eke out a meager living with all manner of work

around the crematoria. It is evident from a commentary upon the Hevajra Tantra

that among other things they there offered themselves to the vagrant yogis

for the latter’s sexual practices (Snellgrove,

1987, vol. 1, p. 168). For an orthodox Hindu such creatures were considered

untouchable. If even the shadow of a candali fell upon a Hindu, the

disastrous consequences were life-long for the latter.

Since it annulled the strict prescriptions of the

Hindu caste system with its rituals, a fundamentally social revolutionary

attitude has been ascribed to Tantric Buddhism. In particular, modern

feminists accredit it with this (Shaw, 1994, p. 62). But, aside from the

obvious fact that women from the lower classes are more readily available

as sexual partners, here too the “law of inversion” is considered decisive

for the choice to be made. The social inferiority of the woman increases

the “antinomism” of the tantric rituals. “It is

the symbol of the ‘washerwoman’ and the ‘courtesan’ [which are] of decisive

significance”, we may read in a book by Mircea Eliade, “and we must familiarize ourselves with the

fact that, in accordance with the tantric doctrine of the identity of

opposites, the ‘most noble and valuable’ is precisely [to be found] hidden

within the ‘basest and most banal’” (Eliade,

1985, p. 261, note 204).

Likewise, when women from the higher castes

(Brahmans, ‘warriors’, or rich business people) are on the Tantric’s wish list, especially when they are married,

the law of inversion functions here as well, since a rigid taboo is broken

through the employment of a wife from the upper classes — an indicator for

the boundless power of the yogi.

The incest taboo

There is indisputable evidence from archaic

societies for the violation of the incest prohibition: there is hardly a tantra of the higher class in which sexual intercourse

with one’s own mother or daughter, with aunts or sisters-in-law is not

encouraged. Here too the German lama Govinda

emphatically protests against taking the texts literally. It would be

downright ridiculous to think “that Tantric Buddhists really did encourage

incest and sexual deviations (Govinda, 1991, p.

113). Mother, sister, daughter and so on stood for the four elements,

egomania, or something similar.

But such symbolic assignments do not necessarily

contradict the possibility of an incestuous praxis, which is in fact found

not just in the Tibet

of old, but also in totally independent cultures scattered all around the

world. Here too, it remains valid that the yogi, who is as a matter of

principle interested in a fundamental violation of proscriptions, must

really long for an incestuous relationship. There is also no lack of historical

reports. We present the curse of a puritanically minded lama from the 16th

century, who addressed the excesses of his libertine colleagues as follows:

“In executing the rites of sexual union the people copulate without regard

to blood relations ... You are more impure than dogs and pigs. As you have

offered the pure gods feces, urine, sperm and blood, you will be reborn in

the swamp of rotten cadavers” (Paz, 1984, p.95).

Eating and drinking impure substances

A central role in the rites is played by the

tantric meal. It is absolutely forbidden for Buddhist monks to eat meat or

drink alcohol. This taboo is also deliberately broken by Vajrayana

adepts. To make the transgression more radical, the consumption of types of

meat which are generally considered “forbidden” in Indian society is

desired: elephant meat, horsemeat, dogflesh,

beef, and human flesh. The latter goes under the name of maha mamsa,

the ‘great flesh’. It usually came from the dead, and is a “meat of those

who died due to their own karma, who were killed in battle due to evil

karma or due to their own fault”, Pundarika

writes in his traditional Kalachakra commentary, and goes on to add that it is

sensible to consume this substance in pill form (Newman, 1987, p. 266).

Small amounts of tit are also recommended in a modern text on the Kalachakra Tantra as

well (Dhargyey, 1985, p. 25). There are recipes

which distinguish between the various body parts and demand the consumption

of brain, liver, lungs, intestines, testes and so forth for particular

ceremonies.

The five taboo types of meat are granted a

sacramental character. Within them are concentrated the energies of the

highest Buddhas, who are able to appear through

the “law of inversion”. The texts thus speak of the “five ambrosias” or

“five nectars”. Other impure “foods” have also been assigned to the five Dhyani Buddhas. Ratnasambhava

is associated with blood, Amitabha with semen, Amoghasiddhi with human

flesh, Aksobhya

with urine, Vairocana

with excrement (Wayman, 1973, p. 116).

The Candamaharosana Tantra lists with relish the particular substances

which are offered to the adept by his wisdom consort during the sexual

magic rituals and which he must swallow: excrement, urine, saliva,

leftovers from between her teeth, lipstick, dish-water, vomit, the wash

water which remains after her anus has been cleaned (George, 1974, pp. 73,

78, 79) Those who “make the excrement and urine their food, will be truly

happy”, promises the Guhyasamaja Tantra

(quoted by Gäng, 1988, p. 134). In the Hevajra Tantra

the adept must drink the menstrual blood of his mudra out of a skull bowl (Farrow and Menon, 1992, p. 98). But rotten fish, sewer water,

canine feces, corpse fat, the excrement of the dead, sanitary napkins as

well as all conceivable “intoxicating drinks” are also consumed (Walker,

1982, pp. 80–84).

There exists a strict commandment that the

practicing yogi may not feel any disgust in consuming these impure

substances. “One should never feel disgusted by excrement, urine, semen or

blood” (quoted by Gäng, 1988, p. 266).

Fundamentally, “he must eat and drink whatever he obtains and he should not

hold any notions regarding likes and dislikes” (Farrow and Menon, 1992, p. 67).

But it is not just in the tantric rites, in

Tibetan medicine as well all manner of human and animal excretions are

employed for healing purposes. The excrement and urine of higher lamas are

sought-after medicines. Processed into pills and offered for sale, they

once played -and now play once more — a significant role in the business

activities of Tibetan and exile-Tibetan monasteries. Naturally, the highest

prices are paid for the excretions of the supreme hierarch, the Dalai Lama.

There is a report on the young Fourteenth god-king’s sojourn in Beijing (in

1954) which recounts how His Holiness’s excrement was collected daily in a

golden pot in order to then be sent to Lhasa and processed into a

medication there (Grunfeld, 1996, p. 22). Even if

this source came from the Chinese camp, it can be given credence without

further ado, since corresponding practices were common throughout the

entire country.

The "feast on fæces fallacy"

As damtsig has come into contact with

Western psychological materialism, self-defence tactics have taken a

variety of forms. The one that has most intrigued me is what I have dubbed

the "feast on fæces fallacy" - of which

there appear to be two variations. I encountered the first during my

introduction to Vajrayana at Vajradhatu

Seminary - a three-month practice and study retreat designed by Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. I attended this retreat after Trungpa Rinpoche's death,

when his son, Sakyong Mipham

Rinpoche, taught it. As the summer progressed and

the teachings grew more challenging, speculation about samaya

heated up. The speculation took on an odd repeating pattern. At some point

in every conversation on the topic, someone would inevitably say, "I

heard that samaya means that if the Sakyong tells you to eat shit, you have to do it."

The conversation would then devolve into everyone deciding whether they

would eat shit or not. After puzzling over it for a while, my eventual

response to this statement was, "How likely is it that the Sakyong would ask you to eat shit?" The whole

discussion was a scare tactic, however unconscious it may have been. It

presented one with an extreme, reductio

ad absurdum proposition from which one could quite justifiably turn

away in disgust. In the process, it just so happened

that one also cut oneself off from finding out what samaya

actually did mean. That version of the Feast on Fæces Fallacy operates by the student scaring himself or herself away from damtsig.

The second variation on this theme operates to discredit the Lama

with whom the student might make the vow. A good example of this was in a

report on the first conference of Western Buddhist teachers with HH Dalai

Lama in Dharamsala in 1993. At one of the

conference sessions, Robert Thurman reportedly said that anyone who allowed

himself or herself to be called a vajra master

should be presented with a plate of excrement and a fork. If he or she was

not capable of eating it, based on the principle of rochig

(ro gcig -

one taste), then he or she was a fraud and should take up knitting. This

politically devious perspective is one which seeks to neuter every Lama who

is not invested with the correct degree of current western adulation.

Evidently a Lama who denies being a vajra master

but who is nonetheless regarded as a vajra master

is exempt from the offer of Robert Thurman's fæcal

feast.

From: The "Feast on Fæces Fallacy" Or - how not to scare oneself away

from liberation - by Nora Cameron in: http://www.damtsig.org/articles/faeces.html

Necrophilia

In a brilliant essay on Tantrism,

the Mexican essayist and poet Octavio Paz drew

attention to the fact that the great fondness of the Mexicans for skeletons

and skulls could be found nowhere else in the world except in the Buddhist

ritual practices of the Tibetans and Nepalese. The difference lies in the

fact that in Mexico the death figures are regarded as a mockery of life and

the living, whilst in Tantrism they are “horrific

and obscene” (Paz, 1984, p. 94). This connection between death and

sexuality is indeed a popular leitmotiv

in Tibetan art. In scroll images the tantric couples are appropriately

equipped with skull bowls and cleavers, wear necklaces of severed heads and

trample around upon corpses whilst holding one another in the embrace of

sexual union.

A general, indeed dominant necrophiliac

strain in Tibetan culture cannot be overlooked. Fokke

Sierksma’s work includes a description of a

meditation cell in which a lama had been immured. It was decorated with

human hair, skin and bones, which were probably supplied by the dismemberers of corpses. Strung on a line were a number

of dried female breasts. The eating bowl of the immured monk was not the

usual human skull, but was also made from the cured skin of a woman’s

breast (Sierksma, 1966, p. 189).

Such macabre ambiences can be dismissed as

marginal excesses, which is indeed what they are in the full sweep of

Tibetan culture. But they nonetheless stand in a deep meaningful and

symbolic connection with the paradoxical philosophy of Tantrism,

of Buddhism in general even, which since its beginnings recommended as

exercises meditation upon corpses in the various stages of decomposition in

order to recognize the transience of all being. Alone the early Buddhist

contempt for life, which locked the gateway to nirvana, is sufficient to understand the regular fascination

with the morbid, the macabre and the decay of the body which characterizes

Lamaism. Crematoria, charnel fields, cemeteries, funeral pyres, graves, but

also places where a murder was carried out or a bloody battle was fought

are considered, in accord with the “law of inversion”, to be especially

suitable locations for the performance of the tantric rites with a wisdom

consort.

The sacred art of Tibet also revels in macabre

subjects. In illustrations of the wrathful deities of the Tibetan pantheon,

their hellish radiation is transferred to the landscape

and the heavens and transform everything into a nature morte in the truest sense of

the word. Black whirlwinds and greenish poisonous vapors sweep across

infertile plains. Deep red rods of lightning flash through the night and

rent clouds, ridden by witches, rage across a pitch black sky. Pieces of

corpses are scattered everywhere, and are gnawed at by all manner of

repulsive beasts of prey.

In order to explain the morbidity of Tibetan

monastic culture, the Dutch cultural psychologist Fokke

Sierksma makes reference to Sigmund Freud’s

concept of a “death wish” (thanatos). Interestingly, a comparison to Buddhism

occurs to the famous psychoanalyst when describing the structure of the necrophiliac urge, which he attributes to, among other

things, the “nirvana principle”. This he understand to be a general desire

for inactivity, rest, resolution, and death, which is claimed to be innate

to all life. But in addition to this, since Freud, the death wish also

exhibits a concrete sadistic and masochistic component. Both attitudes are

expressions of aggression, the one directed outwards (sadism), the other

directed inwardly (masochism).

Ritual murder

The most aggressive form of the externalized death

wish is murder. It remains as the final taboo violation within the tantric

scheme to still be examined. The ritual killing of people to appease the

gods is a sacred deed in many religions. In no sense do such ritual

sacrifices belong to the past, rather they still play a role today, for

example in the tantric Kali cults

of India.

Even children are offered up to the cruel goddess on her bloody altars (Time, August 1997, p. 18). Among the

Buddhist, in particular Tibetan, Tantrics such

acts of violence are not so well-known. We must therefore very carefully

pose the question of whether a ritual murder can here too be a part of the cult activity.

It is certain at least that all the texts of the

Highest Tantra class verbally call for murder.

The adept who seeks refuge in the Dhyani Buddha Akshobya

meditates upon the various forms of hate up to and including aggressive

killing. Of course, in this case too, a taboo violation is to be

transformed in accordance with the “law of inversion” into its opposite,

the attainment of eternal life. Thus, when the Guhyasamaja Tantra

requires of the adept that “he should kill all sentient beings with this

secret thunderbolt” (Wayman, 1977, p. 309), then

— according to doctrine — this should occur so as to free them from

suffering.

It is further seen as an honorable deed to

“deliver” the world from people of whom a yogi knows that they will in

future commit nasty crimes. Thus Padmasambhava,

the founder of Tibetan Buddhism, in his childhood killed a boy whose future

abominable deeds he foresaw.

Maha Siddha Virupa and an impaled human

But it is not just pure compassion or a transformatory intent which lies behind the already

mentioned calls to murder in the tantras, above

all not then when they are directed at the enemies of Buddhism. As, for

example, in the rites of the Hevajra Tantra: “After having announced the intention to

the guru and accomplished beings”, it says there, “perform with mercy the

rite of killing of one who is a non-believer of the teachings of the Buddha

and the detractors of the gurus and Buddhas. One

should emanate such a person, visualizing his form as being upside-down,

vomiting blood, trembling and with hair in disarray. Imagine a blazing

needle entering his back. Then by envisioning the seed-syllable of the Fire

element in his heart he is killed instantly” (quoted by Farrow and Menon, 1992, p. 276). The Guhyasamaja Tantra

also offers instructions on how to — as in voodoo magic — create images of

the opponent and inflict “murderous” injuries upon these, which then

actually occur in reality: “One draws a man or a woman in chalk or charcoal

or similar. One projects an ax in the hand. Then one projects the way in

which the throat is slit” (quoted by Gäng, 1988,

p. 225). At another point the enemy is bewitched, poisoned, enslaved, or

paralyzed. Corresponding sentences are to be found in the Kalachakra Tantra.

There too the adept is urged to murder a being which has violated the

Buddhist teachings. The text requires, however, that this be carried out

with compassion (Dalai Lama XIV, 1985, p. 349).

The destruction of opponents via magical means is

part of the basic training of any tantric adept. For example, we learn from

the Hevajra Tantra a

magic spell with the help of which all the soldiers of an enemy army can be

decapitated at one stroke (Farrow and Menon,

1992, p. 30). There we can also find how to produce a blazing fever in the

enemy’s body and let it be vaporized (Farrow and Menon,

1992, p. 31). Such magical killing practices were — as we shall show –in no

sense marginal to Tibetan religious history, rather they gained entry to

the broad-scale politics of the Dalai Lamas.

The destructive rage does not even shy away from

titans, gods, or Buddhas. In contrast, through

the destruction of the highest beings the Tantric absorbs their power and

becomes an arch-god. Even here things sometimes take a sadistic turn, as

for example in the Guhyasamaja Tantra,

where the murder of a Buddha is demanded: “One douses him in blood, one

douses him in water, one douses him in excrement and urine, one turns him

over, stamps on his member, then one makes use of the King of Wrath. If

this is completed eight hundred times then even a Buddha is certain to

disintegrate” (quoted by Gäng, 1988, p. 219).

In order to effectively perform this Buddha

murder, the yogi invokes an entire pandemonium, whose grotesque appearance

could have been modeled on a work by Hieronymus Bosch: “He projects the

threat of demons, manifold, raw, horrible, hardened

by rage. Through this even the diamond bearer [the Highest Buddha] dies. He

projects how he is eaten by owls, crows, by rutting vultures with long

beaks. Thus even the Buddha is destroyed with certainty. A black snake,

extremely brutish, which makes the fearful be

afraid. ... It rears up, higher than the forehead. Consumed by this snake

even the Buddha is destroyed with certainty. One lets the the perils and torments of all beings in the ten

directions descend upon the enemy. This is the best. The is

the supreme type of invocation” (quoted by Gäng,

1988, p. 230). This can be strengthened with the following aggressive

mantra: “Om, throttle, throttle, stand, stand, bind, bind, slay, slay,

burn, burn, bellow, bellow, blast, blast the leader of all adversity,

prince of the great horde, bring the life to an end” (quoted by Gäng, 1988, p. 230).

We encounter a particularly interesting murder

fantasy in the deliberate staging of the Oedipus drama which a passage from

the Candamaharosana Tantra

requires. The adept should slay Aksobhya, his

Buddha father, with a sword, give

his mother, Mamaki, the flesh of the murdered father

to eat and have sexual intercourse with her afterwards (George, 1974, p.

59; Filliozat, 1991, p. 430).

Within the spectrum of Buddhist/tantric killing

practices, the deliberately staged “suicide” of the “sevenfold born”

represents a specialty. We are dealing here with a person who has been

reincarnated seven times and displays exceptional qualities of character.

He speaks with a pleasant voice, observes with beautiful eyes and possesses

a fine-smelling and glowing body which casts seven shadows. He never

becomes angry and his mind is constantly filled with infinite compassion.

Consuming the flesh of such a wonderful person has the greatest magical

effects.

Hence, the Tantric should offer a “sevenfold born”

veneration with flowers and ask him to act in the interests of all

suffering beings. Thereupon — it says in the relevant texts — he will

without hesitation surrender his own life. Afterwards pills are to be made

from his flesh, the consumption of which grant among other things the siddhis

(powers) of ‘sky-walking’. Such pills are in fact still being distributed

today. The heart-blood is especially sought after, and the skull of the

killed blessed one also possesses magical powers (Farrow and Menon, 1992, p. 142).

When one considers the suicide request made to the

“sevenfold born”, the cynical structure of the tantric system becomes

especially clear. His flesh is so yearned-for because he exhibits that

innocence which the Tantric on account of his contamination with all the

base elements of the world of appearances no longer possesses. The

“sevenfold born” is the complete opposite of an adept, who has had dealings

with the dark forces of the demonic. In order to transform himself through

the blissful flesh of an innocent, the yogi requests such a one to

deliberately sacrifice himself. And the higher

being is so kind that it actually responds to this request and afterwards

makes his dead body available for sacred consumption.

The mystery of the eucharist,

in which the body and blood of Christ is divided among his believers

springs so readily to mind that it is not impossible that the tantric

consumption of a “sevenfold born” represents a Buddhist paraphrase of the

Christian Last Supper. (The tantras appeared in

the 4th century C.E. at the earliest.) But such self-sacrificial scenes can

also be found already in Mahayana

Buddhism. In the Sutra of Perfected

Wisdom in Eight Thousand Verses a description can be found of how the

Bodhisattva Sadaprarudita dismembers his own body

in order to worship his teacher. Firstly he slits both his arms so that the

blood pours out. Then he slices the flesh from his legs and finally breaks

his own bones so as to be able to also offer the marrow as a gift. Whatever

opinion one has of such ecstatic acts of self-dismemberment, in Mahayana they always demonstrate the

heroic deed of an ethically superior being who wishes to help others. In

contrast, the cynical sacrifice of the “sevenfold born” demonstrates the

exploitation of a noble and selfless sentiment to serve the power interests

of the Tantric. In the face of such base motives, the Tibet

researcher David Snellgrove with some

justification doubts the sevenfold incarnated’s

imputed preparedness to be sacrificed: “Did one track him down and wait for

him to die or did one hasten the process? All these tantras

give so many fierce rites with the object of slaying, that the second

alternative might not seem unlikely ...” (Snellgrove,

1987, vol. 1, p. 161).

Symbol and reality

Taking Snellgrove’s

suspicion as our starting point, the question arises as to whether the

ritual murder of a person is intended to be real or just symbolic in the

tantric scripts. Among Western interpreters of the tantras

opinions are divided. Early researchers such as Austine

Waddell or Albert Grünwedel presumed a literal

interpretation of the rituals described in the texts and were dismayed by

them. Among contemporary authors, especially those who are themselves

Buddhists, the “crimes” of Vajrayana are usually played down as allegorical

metaphors, as Michael M. Broido or Anagarika Govinda do in their

publications, for example. This toned-down point of view is, for readily

understandable reasons, today thankfully adopted by Tibetan lamas teaching

everywhere in the Western world. It liberates the gurus from tiresome

confrontations with the ethical norms of the cultures in which they have

settled after their flight from Tibet. They too now see

themselves called to transform the offensive shady sides of the tantras into friendly bright sides: “Human flesh” for

example is to be understood as referring to the own imperfect self which

the yogi “consumes” in a figurative sense through his sacred practices. “To

kill” means to rob dualistic thought patterns of their life in order to

recreate the original unity with the universe, and so forth. But despite

such euphemisms an unpleasant taste remains, since the statements of the tantras are so unequivocal and clear.

It is at any rate a fact that the entire tantric

ritual schema does not get by without dead body parts and makes generous

use of them. The sacred objects employed consist of human organs, flesh,

and bones. Normally these are found at and collected from the public

crematoria in India

or the charnel fields of Tibet.

But there are indications which must be taken

seriously that up until this century Tibetans have had to surrender their

lives for ritualistic reasons. The (fourteenth-century) Blue Annals, a seminal document in

the history of Tibetan Buddhism, already reports upon how in Tibet the

so-called “18 robber-monks” slaughtered men and women for their tantric

ceremonies (Blue Annals, 1995, p.

697). The Englishman Sir Charles Bell visited a stupa

on the Bhutan-Tibet border in which the ritually killed body of an

eight-year-old boy and a girl of the same age were found (Bell, 1927, p.

80). Attestations of human sacrifice in the Himalayas

recorded by the American anthropologist Robert Ekvall

date from the 1950s (Ekvall, 1964, pp. 165–166,

169, 172).

In their criticism of lamaism,

the Chinese make frequent and emphatic reference to such ritual killing

practices, which were still widespread at the time of the so-called

“liberation” of the country, that is until the end

of the 1950s. According to them, in the year 1948 21individuals were

murdered by state sacrificial priests from Lhasa as part of a ritual of enemy

destruction, because their organs were required as magical ingredients (Grunfeld, 1996, p. 29). Rather than dismissing such

statements in advance as evil communist propaganda, the original spirit of

the tantra texts would seem to afford that they

be investigated conscientiously and without prejudice.

The morbid ritual objects on display in the Tibetan Revolutions

Museum

established by the Chinese in Lhasa,

certainly teach us something about horror: prepared skulls, mummified

hands, rosaries made of human bones, ten trumpets made from the thigh bones

of 16-year-old girls, and so on. Among the museum’s exhibits is also a

document which bears the seal of the (Thirteenth or Fourteenth?) Dalai Lama

in which he demands the contribution of human heads, blood, flesh, fat,

intestines, and right hands, likewise the skins of children, the menstrual

blood of a widow, and stones with which human skulls had been staved in, for the “strengthening of holy order”

(Epstein, 1983, p.138). Further, a small parcel of severed and prepared

male sexual organs which are needed to conduct certain rituals can also be

seen there, as well as the charred body of a young woman who was burned as

a witch. If the tantra texts did not themselves

mention such macabre requisites, it would never occur to one to take this

demonstration of religious violence seriously.

That the Chinese with their accusations of tantric

excesses cannot be all that false, is demonstrated

by the relatively recent brutal murder of three lamas, which deeply shook

the exile-Tibetan community in Dharamsala. On 4 February 1997, the

murdered bodies of the 70-year-old lama Lobsang Gyatso, head of the Buddhist-dialectical school, and

two of his pupils were found just a few yards from the residence of the

Fourteenth Dalai Lama. The murderers had repeatedly stabbed their victims

with a knife, had slit their throats and according to press reports had

partially skinned their corpses (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 1997, no. 158, p. 10). All the observers

and commentators on the case were of the unanimous opinion that this was a

case of ritual murder. In the second part of our analysis we examine in

detail the real and symbolic background and political implications of the

events of 4 February.

At any rate, the supreme demands which a yogi must

make of himself in order to expose a “crime” which he “really” commits as

an illusion speaks for the likelihood of the actual staging of a killing

during a tantric ritual. In the final instance the conception that

everything is only an illusion and has no independent existence leads to an indifference as to whether a murder is real or “just”

allegorical. From this point of view everything in the world of Vajrayana is

both “real” and “symbolic”. “We touch symbols, when we think we are

touching bodies and material objects”, writes Octavio

Paz with regard to Tantrism, “And vice versa:

according to the law of reversibility all symbols are real and touchable,

ideas and even nothingness has a taste. It makes no difference whether the

crime is real or symbolic: Reality and symbol fuse, and in fusing they

dissolve” (Paz, 1984, pp. 91–92).

Concurrence with the demonic

The excesses of Tantrism

are legitimated by the claim that the yogi is capable of transforming evil

into good via his spiritual techniques. This inordinate

attempt nonetheless give rise to apprehensions as to whether the

adept does in fact have the strength to resist all the temptations of the

“devil”? Indeed, the “law of inversion” always leads in the first phase to

a “concurrence with the demonic” and regards contact with the “devil” as a

proper admission test for the path of enlightenment. No other current in

any of the world religions thus ranks the demons and their retinue so highly as in Vajrayana.

The image packed iconography of Tibet

literally teems with terrible deities (herukas) and red henchmen.

When one dares, one’s gaze is met by disfigured faces, hate-filled

grimaces, bloodshot eyes, protruding canines. Twisted sneers leave one

trembling — at once both terrible and wonderful, as in an oriental

fairy-tale. Surrounded by ravens and owls, embraced by snakes and animal

skins, the male and female monster gods carry battle-axes, swords, pikes

and other murderous cult symbols in their hands, ready at any moment to cut

their opponent into a thousand pieces.

The so-called “books of the dead” and other ritual

text are also storehouses for all manner of zombies, people-eaters, ghosts,

ghouls, furies and fiends. In the Guhyasamaja Tantra the concurrence of the Buddhas

with the demonic and evil is elevated to an explicit part of the program:

“They constantly eat blood and scraps of flesh ... They drink treachery

like milk ... skulls, bones, smokehouses, oil and fat bring great joy”

(quoted by Gäng, 1988, pp. 259–260). In this

document the Buddhist gods give free rein to their aggressive destructive

fantasies: “Hack to pieces, hack to pieces, sever, sever, strike, strike,

burn, burn” they urge the initands with furious

voices (quoted by Gäng, 1988, p. 220). One could

almost believe oneself to be confronted with primordial chaos. Such horror

visions are not just encountered by the tantric adept. They also, in

Tibetan Buddhist tradition, appear to every normal person, sometimes during

a lifetime on earth, but after death inevitably. Upon dying every deceased

person must, unless he is already enlightened, progress through a limbo (Bardo) in

which bands of devils sadistically torment him and attempt to pull the wool

over his eyes. As in the Christian Middle Ages, the Tibetan monks’

fantasies also revel in unbearable images of hell. It is said that not even

a Bodhisattva is permitted to help a person out of the hell of Vajra (Trungpa, 1992, p. 68).

Here too we would like to come up with a lengthier

description, in order to draw attention to the anachronistic-excruciating

world view of Tantric Buddhism: “The souls are boiled in great cauldrons,

inserted into iron caskets surrounded by flames, plunge into icy water and

caves of ice, wade through rivers of fire or swamps filled with poisonous

adders. Some are sawed to pieces by demonic henchmen, others plucked at

with glowing tongs, gnawed by vermin, or wander lost through a forest with a foliage of razor sharp daggers and swords. The tongues

of those who blasphemed against the teaching grow as big as a field and the

devils plow upon them. The hypocrites are crushed beneath huge loads of

holy books and towering piles of relics” (Bleichsteiner,

1937, p. 224). There are a total of 18 different hells, one more dreadful

than the next. Above all, the most brutal punishments are reserved for

those “sinners” who have contravened the rules of Vajrayana. They can wait for

their “head and heart [to] burst” (Henss, 1985,

p. 46).

A glance at old Tibetan criminal law reveals that

such visions of fear and horror also achieved some access to social

reality. Its methods of torture and devious forms of punishment were in no

way inferior to the Chinese cruelties now denounced everywhere: for

example, both hands of thieves were mutilated by being locked into

salt-filled leather pouches. The amputation of limbs and bloody floggings

on the public squares of Lhasa,

deliberately staged freezing to death, shackling, the fitting of a yoke and

many other “medieval” torments were to be found in the penal code until

well into the 20th century. Western travelers report with horror and

loathing of the dark and damp dungeons of the Potala,

the official residence of the Dalai Lamas.

This clear familiarity with the spectacle of hell

in a religion which bears the banners of love and kindness, peace and

compassion is shocking for an outsider. It is only the paradoxicalness

of the tantras and the Madhyamika philosophy (the

doctrine of the ‘emptiness’ of all being) which allows the rapid interplay

between heaven and hell which characterizes Tibetan culture. Every lama

will answer that, “since everything is pure illusion, that must also be the

case for the world of demons”, should one ask him about the devilish

ghosts. He will indicate that it is the ethical task of Buddhism to free

people from this world of horrors. But only when one has courageously

looked the demon in the eye, can he be exposed as illusory or as a ghostly

figure thrown up by one’s own consciousness.

Nevertheless, that the obsessive and continuous

preoccupation with the terrible is motivated by such therapeutic intentions

and philosophical speculations is difficult to comprehend. The demonic is

accorded a disturbingly high intrinsic value in Tibetan culture, which

influences all social spheres and possesses a seamless tradition. When Padmasambhava converted Tibet to Buddhism in the eighth

century, the sagas recount that he was opposed by numerous native male and

female devils, against all of whom he was victorious thanks to his skills

in magic. But despite his victory he never killed them, and instead forced

them to swear to serve Buddhism as protective spirits (dharmapalas) in future.

Why, we have to ask ourselves, was this horde of

demons snorting with rage not transformed via the tantric “law of

inversion” into a collection of peace-loving and graceful beings? Would it

not have been sensible for them to have abandoned their aggressive

character in order to lead a peaceful and dispassionate life in the manner

of the Buddha Shakyamuni? The opposite was the

case — the newly “acquired” Buddhist protective gods (dharmapalas) had not just the

chance but also the duty to live out their innate aggressiveness to the

full. This was even

multiplied, but was no longer directed at orthodox Buddhists

and instead acted to crush the “enemies of the teaching”. The atavistic

pandemonium of the pre-Buddhist Land

of Snows survived as

a powerful faction within the tantric pantheon and, since horror in general

exercises a greater power of fascination than a “boring” vision of peace,

deeply determined Tibetan cultural life.

Many Tibetans — among them, as we shall later see,

the Fourteenth Dalai Lama — still believe themselves to be constantly

threatened by demonic powers, and are kept busy holding back the dark

forces with the help of magic, supplicatory

prayers, and liturgical techniques, but also recruiting them for their own

ends, all of which incidentally provides a considerable source of income

for the professional exorcists among the lamas. Directly alongside this underworldly abyss — at least in the imagination — a

mystic citadel of pure peace and eternal rest rises up, of which there is

much talk in the sacred writings. Both visions — that of horror and that of

bliss — complement one another and are in Tantrism

linked in a “theological” causal relationship which says that heaven may

only be entered after one has journeyed through hell.

In his psychoanalytical study of Tibetan culture, Fokke Sierksma conjectures

that the chronic fear of demonic attacks was spread by the lamas to help

maintain their power and, further to this, is blended with a

sadomasochistic delight in the macabre and aggressive. The enjoyment of

cruelty widespread among the monks is legitimated by, among other things,

the fact that — as can be read in the tantra

texts — even the Highest Buddhas can assume the

forms of cruel gods (herukas)

to then, bellowing and full of hate, smash everything to pieces.

These days a smile is raised by the observations

of the Briton Austine Waddells,

who, in his famous book published in 1899, The Buddhism in Tibet, drew attention to the general fear which

then dominated every aspect of religious life in Tibet: “The priests must

be constantly called in to appease the menacing devils, whose ravenous

appetite is only sharpened by the food given to stay it” (quoted by Sierksma, 1966, p. 164). However, Waddell’s images of

horror were confirmed a number of decades later by the Tibetologist

Guiseppe Tucci, whose

scholarly credibility cannot be doubted: “The entire spiritual life of the

Tibetans”, Tucci writes, “is defined by a

permanent attitude of defense, by a constant effort to appease and

propitiate the powers whom he fears” (Grunfeld,

1996, p. 26).

There is no need for us to rely solely on Western

interpreters in order to demonstrate Tantrism’s

demonic orientation; rather we can form an impression for ourselves. Even a

fleeting examination of the violent tantric iconography confirms that

horror is a determining element of the doctrine. Why do the “divine” demons

on the thangkas only very seldom take to the

field against one another but rather almost exclusively mow down men,

women, and children? What motivates the “peace-loving” Dalai Lama to choose

as his principal protective goddess a maniacal woman by the name of Palden Lhamo,

who rides day and night through a boiling sea of blood? The fearsome

goddess is seated upon a saddle which she herself personally crafted from

the skin of her own son. She murdered him in cold blood because he refused

to follow in the footsteps of his converted mother and become a Buddhist.

Why — we must also ask ourselves — has the militant war god Begtse been

so highly revered for centuries in the Tibetan monasteries of all sects?

One might believe that this “familiarity with the

demonic” would by the end of the 20th century have changed among

the exile Tibetans, who are praised for their “open-mindedness”. Unfortunately,

many events of which we come to speak of in the second part of our study,

but most especially the recent and already mentioned ritual murders of 4 February 1997 in Dharamsala, illustrate that the gates of hell are by no

means bolted shut. According to reports so far, the perpetrators were

acting on behalf of the aggressive protective spirit, Dorje Shugden. Even the Fourteenth Dalai

Lama has attributed to this dharmapala (protective deity) the power to threaten his

life and to bewitch him by magical means.

If horror is acceptable, then death is cheap. It

is true that in Tantrism death is considered to

be a state of consciousness which can be surmounted, but in Tibetan culture

(which also incorporates non-tantric elements) like the demons it has also

achieved a thriving “life of its own” and enjoys general cult worship.

There — as we shall often come to show — it stands at the center of

numerous macabre rites. Sigmund Freud’s problematic formulation, that “the

goal of all life is death” can in our view be prefaced to Lamaism as its leitmotiv.

The aggression of the divine couple

Does this iconography of horror also apply to the

divine couple who are worshipped at the heart of the tantric rituals? On

the basis of the already described apotheosis of mystic sexual love as the

suspension of all opposites, as a creative polarity, as the origin of

language, the gods, time, of compassion, emptiness, and of the white light

we ought to assume that the primal couple radiate peace, harmony, concord,

and joy. In fact there are such blissful illustrations of the love of god

and goddess in Tantrism. In this connection the

primal Buddha, Samantabhadra, highly revered in the Nyingmapa school, deserves special mention; naked he

sits in the meditative posture without any ritual objects in his hands,

embracing his similarly unclothed partner, Samantabhadri. This pure

nakedness of the loving couple demonstrates a powerful vision, which breaks

through the otherwise usual patriarchal relation of dominance which

prevails between the sexes. All other images of the Buddhas

with their consorts express an androcentric

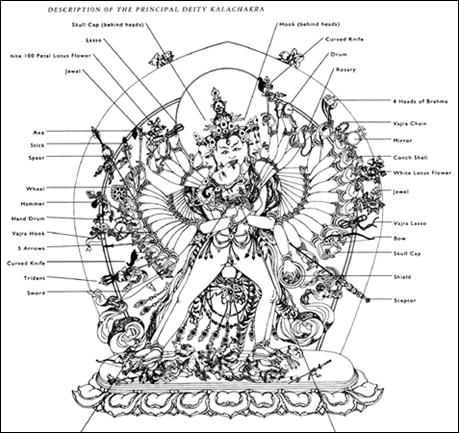

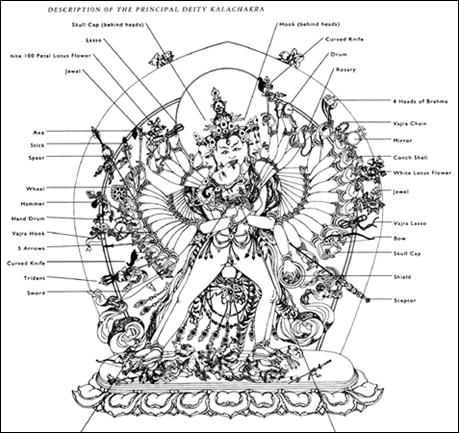

gesture of dominance through the symbolic objects assigned to them. [1]

The implements of the deity Kalachakra and his consort Vishvamata

Peaceful images of the divine couple are, however,

exceptional within the Highest Tantras and in no

way the rule. The majority of the yab–yum

representations are of the Heruka type,

that is, they show couples in furious, destructive and violent positions.

Above all the Buddha Hevajra

and his consort Nairatmya.

Surrounded by eight “burning” dakinis he performs

a bizarre dance of hell and is so intoxicated by his killing instinct that

he holds a skull bowl in each of his sixteen hands, in which gods, humans,

and animals are to be found as victims. In her right hand Nairatmya

threateningly swings a cleaver. Raktiamari, Yamantaka, Cakrasamvara, Vajrakila or whatever names the clusters of pairs

from the other tantras may have, all of them

exhibit the same striking mixture of aggressiveness, thanatos,

and erotic love.

Likewise, the time god, Kalachakra, is of the heruka

type. His wildness is underlined by his vampire-like canines and his hair

which stands on end. The tiger pelt draped around his hips also signalizes

his aggressive character. Two of his four faces are not peaceful, but

instead express greed and wrath. But above all his destructive attitude is

emphasized by the symbols which the “Lord of Time” holds in his twenty-four

hands. Of these, six are of a peaceful nature and eighteen are warlike.

Among the latter are the vajra, vajra hook, sword, trident, cleaver, damaru (a drum made from two

skull bowls), kapala

(a vessel made out of a human skull), khatvanga (a type of scepter,

the tip of which is decorated with three severed human heads), ax, discus,

switch, shield, ankusha

(elephant hook), arrow, bow, sling, prayer beads made from human bones as

well as the severed heads of Brahma.

The peaceable symbols are: a jewel, lotus, white conch shell, triratna

(triple jewel), and fire, so long it is not used destructively. Finally,

there is the bell.

His consort, Vishvamata, also fails to make a pacifist

impression. Of the eight symbolic objects which she holds in her eight

hands, six are aggressive or morbid, and only two, the lotus and the triple

jewel, signify happiness and well-being. Among her magical defense weapons

are the cleaver, vajra

hook, a drum made from human skulls, skull bowls filled with hot blood, and

prayer beads made out of human bones. To signalize that she is under the

control of the androcentric principle, each of

her four heads bears a crown consisting of a small figure who represents the male Dhyani

Buddha, Vajrasattva.

As far as the facial expressions of the time goddess can be deciphered,

above all they express sexual greed.

Both principal deities, Kalachakra and Vishvamata, stand joined in

union in the so-called at-ease stance, which is supposed to indicate their

preparedness for battle and willingness to attack. The foundation is

composed of four cushions. Two of these symbolize the sun and moon, the

other two the imaginary planets, Rahu and Kaligni. Rahu is believed to swallow both of the former

heavenly bodies and plays a role within the Kalachakra rituals which is

just as prominent as that of Kaligni, the apocalyptic fire which destroys the world

with flame. The two planets thus have an extremely aggressive and

destructive nature. Beneath the feet of the time couple two Hindu gods are

typically shown being trampled, the red love god Kama and the white terror god Rudra. Their two partners, Rati and Uma, try in vain to rescue them.

Consequently, the entire scenario of the Kalachakra Tantra is

warlike, provocative, morbid, and hot-tempered. In examining its

iconography, one constantly has the feeling of being witness to a massacre.

It is no help against this when the many commentaries stress again and

again that aggressive ritual objects, combative body postures, expressions

of rage, and wrathful deeds are necessary in order to surmount obstacles

which block the individual’s path to enlightenment. Nor, in light of the

pathological compulsiveness with which the Tantric attempts to drive out

horror with horror, is the affirmation convincing, that Buddha’s wrath is

compensated for by Buddha’s love and that all this cruelty is for the

benefit of all suffering beings.

The aggressiveness of both partners in the tantras remains a puzzle. To our knowledge it is not

openly discussed anywhere, but rather accepted mutely. In the Highest Tantras we can all but assume the principle that the

loving couple as the wrathful- warlike and turbulent element finds its

counterpoint in a peaceful and unmoving Buddha in meditative posture. In

the light of this tantric iconography one has the impression that the vajra master

prefers a hot and aggressive sexuality with which to effect the

transformation of erotic love into power. Perhaps the Dutch psychologist, Fokke Sierksma, did not lie

so wide of the mark when he described the tantric performance as

“sadomasochistic”, whereby the sadistic role is primarily played by the

man, whilst the woman exhibits both compulsions together. At any rate, the

energy set free by “hot sex” appears to be an especially sought-after

substance for the yogis’ “alchemic” transformative games, which we will

come to examine in more detail later in the course of our study.

The poetry and beauty of mystic sexual love is far

more often (even if not at all consistently) expressed in the words of the

Highest Tantra texts, than in the visual

representations of a morbid tantric eroticism. This does not fit together

somehow. Since at the end of the sexual magic rituals the masculine

principle alone remains, the verbal praise of the goddess, beauty and love

could also be manipulative, designed to conjure up the devotion of a woman.

Bearing in mind that the method (upaya) of the yogis can also be translated as “trick”,

we may not exclude such a possibility.

Western criticism

In the light of the unconcealed potential for

violence and manifest obsessions with power within Tantric Buddhism it is

incomprehensible that the idea has spread, even among many Western authors

and a huge public too, that Vajrayana is a religious practice which exclusively

promotes peace. This seems all the more misled since the whole system in no

way denies its own destructiveness and draws its entire power from the

exploitation of extremes. In the face of such inconsistencies, some keen

interpreters of the tantras project the violent

Buddhist fantasies outwards, by making Hinduism and the West responsible

for aggression and hunger for power.

For example, the Tibetologist

of German origins, Herbert Guenther (born 1917), who has been engaged in an

attempt to win philosophical respectability for Vajrayana in Europe and

America since the 60s, sharply attacks the Western and Hindu cultures:

“this purely Hinduistic power mentality, so

similar to the Western dominance psychology, was generalized and applied to

all forms of Tantrism by writers who did not see

or, due to their being steeped so much in dominance psychology, could not

understand that the desire to realize Being is not the same as the craving

for power” (Guenther, 1976, p. 64). The sacred eroticism of Buddhism is

completely misunderstood in the west and interpreted as sexual pleasure and

exploitation. “The use of sexuality as a tool of power destroys its

function”, this author tells us and continues, “Buddhist Tantrism dispenses with the idea of power, in which it

sees a remnant of subjectivistic philosophy, and

even goes beyond mere pleasure to the enjoyment of being and of

enlightenment unattainable without woman” (Guenther, 1976, 66).

Anagarika Govinda

(1898-1985), also a German converted to Buddhism whose original name was

Ernst Lothar Hoffmann and who believed himself to be a reincarnation of the German romantic Novalis, made even greater efforts to deny a claim to

power in Tibetan Buddhism. He even attempted, with — when one considers the

print run of his books — obviously great success, to cleanse Vajrayana of

its sacred sexuality and present it as a pure, spiritual school of wisdom.

Govinda also gives the Hindus the blame for everything

bad about the tantras. Shakti — the German lama says — mean power. “United with Shakti, be full of power!”, it says in a Hindu tantra (Govinda, 1984, p. 106). “The concept of Shakti, of

divine power,” — the author continues — “plays absolutely no role in

Buddhism. Whilst in tantric Hinduism the concept of power lies at the

center of concern” (Govinda, 1984, p. 105).

Further, we are told, the Tibetan yogi is free of all sexual and power

fantasies. He attains union exclusively with the “eternal feminine”, the

symbol for “emotion, love, heart, and compassion”. “In this state there is

no longer anything ‘sexual’ in the time-honored sense of the word ...” (Govinda, 1984, p. 111).

Yet the feminist critique of Vajrayana, which Miranda Shaw

presented in her book on “Women in Tantric Buddhism” published in 1994, appears even more odd.

With reference to Herbert Guenther she also judges the interpretation of

authors who reveal Tantrism to be a sexual and

spiritual exploitation of the woman, to be a maneuver of “western dominance

psychology”. These “androcentric” scholars

reiterate a prejudice embedded deeply within western culture, which says

that men are always active, women in contrast passive victims; men are

power conscious, women are powerless; men are molded by intellect, women by

emotion. It was suggested that women did not posses

the capacity to practice tantric Yoga (Shaw, 1994, p. 9).

It is no surprise that the “militant Tantric”

Miranda Shaw argues thus, then from the first to the last line of her

committed book she tries to bring the proof that women were in no way

inferior to the great gurus and Maha Siddhas. The

apparently meager number of “yoginis” to be found

in the history of Vajrayana, compared that is to the literally

countless assembly of tantric masters, are built up by the author into a

spiritual, female super-elite. The women from the founding phase of Tantrism — we learn here — did not just work together

with their male partners as equals, rather they were far superior to them

in their knowledge of mysteries. They are the actual “masters” and Tantric

Buddhism owes its very existence to them. This radical feminist attempt to

interpret Tantrism as an originally matriarchal

cult event, is however, not entirely unjustified. Let us briefly trace its

footsteps.

Footnotes:

[1] In the usual yab–yum

representation of the Dhyani Buddhas,

the male Buddha figure always crosses both of his arms behind the back of

his wisdom consort, forming what is known

as the Vajrahumkara gesture. At the same time he holds a vajra (the

supreme symbol of masculinity) in his right hand,

and a gantha

(the supreme symbol of femininity) in his left. The symbolic possession of both ritual

objects identifies him as the lord of both sexes. He is the androgyne and the prajna is a part of his self.

Next Chapter:

|