|

© Victor

& Victoria Trimondi

The

Shadow of the Dalai Lama – Part II – 5. Buddhocracy

and anarchy: contradictory or complementary?

5. BUDDHOCRACY AND ANARCHY: CONTRATICTORY OR COMPLEMENTRAY?

The grand sorcerers (Maha Siddhas)

The anarchistic founding father of Tibetan Buddhism: Padmasambhava

From anarchy to discipline of the order: the Tilopa lineage

The pre-ordained counter world to the clerical

bureaucracy: holy fools

An anarchistic erotic: the VI Dalai Lama

A tantric history of Tibet

Crazy wisdom and the West

The totalitarian Lamaist

state (the Tibetan Buddhocracy), headed by its

absolute ruler, the Dalai Lama, was — as contradictory as this may at first

appearance seem to be — only one of the power-political forces which

decisively shaped the history of Tibet. On the other side we find all the

disintegrative and anti-state forces which constantly challenged the

clerical sphere as dangerous opponents. As we shall soon see, within the

whole social structure they represented the forces of anarchy: „Thus, Tibetans understand power both“, writes

Rebecca Redwood French, „as a highly centralized, rigidly controlled and

hierarchically determined force and as a diffuse and multivalent force”

(Redwood French, 1995, p. 108). What are these „diffuse and multivalent”

forces and how does the „highly centralized … and hierarchically

determined” Buddhist state deal with them?

The powers which rebelled against the established

monastic order in the Tibet

of old were legion — above all the all-powerful nature of the country. Extreme climatic conditions and the huge

territory, barely developed in terms of transport

logistics, rendered effective state control by the lamas only partially

realizable. But the problems were not just of the factual kind. In

addition, from the Tibetan, animist point of view, the wilds of nature are

inhabited by countless gods, demons, and spirits, who must all be brought

under control: the lu

— water spirits which contaminate wells and divert rivers; the nyen — tree

spirits that cause illnesses, especially cancer; the jepo — the harmful ghosts of bad kings and lamas who broke their

vows; the black dü

— open rebels who deliberately turn against the Dharma; the mamo, also black — a dangerous breed of

witches and harpies; the sa — evil astral demons; and many others. They all posed

a daily threat for body and soul, life and possession in the Tibet of

old and had to be kept in check through constant rituals and incantations.

This animist world view is still alive and well today despite Chinese communist

materialism and rationalism and is currently experiencing an outright

renaissance.

But it was not enough to have conquered and

enchained (mostly via magic rituals) the nature spirits listed. They then

required constant guarding and supervision so that they did resume their

mischief. Even the deities known as dharmapalas, who were supposed to protect the Buddhist

teachings, tended to forget their duties from to time and turn against

their masters (the lamas). This “omnipresence of the demonic” kept the

monks and the populace in a constant state of alarm and caused an extreme

tension within the Tibetan culture.

On the social

level it was, among other things, the high degree of criminality which time

and again provoked Tibetan state Buddhism and was seen as subversive. The

majority of westerners traveling in Tibet (in the time before the

Chinese occupation) reported that the brigandry

in the country represented a general nuisance. Certain nomadic tribes, the Khampas for example, regarded robbery as a lucrative

auxiliary income or even devoted themselves to it full-time. They were

admittedly feared but definitely not despised for this, but were rather

seen as the heroes of a robber romanticism

widespread in the country. To go out without servants and unarmed was also

considered dangerous in the Lhasa

of old. One lived in constant fear of being held up.

In terms of popular

culture, there were strong

currents of an original, anarchist (non-Buddhist) shamanism which coursed

through the whole country and were not so easily brought under the umbrella

of a Buddhist concept of state. The same was true of the Nyingmapa sect, whose members had a very libertarian

and vagabond lifestyle. In addition, there were the wandering yogis and

ascetics as further representatives of “anarchy”. And last not least, the

great orders conducted an unrelenting competitive campaign against one

another which was capable of bringing the entire state to the edge of

chaos. If, for example, the Sakyapas were at the high point of their

power, then the Kagyupas would lay in wait so as

to discover their weaknesses and bring them down. If the Kagyupas seized control over the Land of Snows,

then they would be hampered by the Gelugpas with

help from the Mongolians.

The Lamaist state and

anarchy have always stood opposed to one another in Tibetan history. But

can we therefore say that Buddhism always and without fail took on the role

of the state which found itself in constant conflict with all the non-Buddhist forces of anarchy? We

shall see that the social dynamic was more complex than this. Tantric

Buddhism is itself — as a result of the lifestyle which the tantras require — an expression of “anarchy”, but only

partially and only at times. In the final instance it succeeds in combining

both the authoritarian state and an anarchic lifestyle, or, to put it

better, in Tibet

(and now in the West) the lamas have developed an ingenious concept and

practice through which to use anarchy to shore up the Buddhocracy.

Let us examine this more closely through a description of the lives of

various tantric “anarchists”.

The grand sorcerers (Maha Siddhas)

The anarchist element in the Buddhist landscape is

definitely not unique to Tibet.

The founding father, Shakyamuni himself,

displayed an extremely anti-state and antisocial behavior and later

required the same from his followers.

Instead of taking up his inheritance as a royal

ruler, he chose homelessness; instead of opting for his wife and harem, he

chose abstinence; instead of wealth he sought poverty. But the actual

“anarchist” representatives of Buddhism are the 84 grand sorcerers or Maha Siddhas,

who make up the legendary founding group of Vajrayana and from whom the

various lineages of Tibetan Buddhism are traced. Hence, in order to

consider the origins of the anti-state currents in Tibetan history, we must

cast a glance over the border into ancient India.

All of the stories about the Maha Siddhas tell of the spectacular

adventures they had to go through to attain their goal of enlightenment

(i.e., the ritual absorption of gynergy). Had they succeeded in this, then they could

refer to themselves as “masters of the maha mudra”. The number of 84 does not

correspond to any historical reality. Rather, we are dealing with a

mystical number here which in symbolizes perfection in several Indian

religious systems. Four of the Maha Siddhas were women. They all lived in India

between the eighth and twelfth centuries.

The majority of these grand sorcerers came from

the lower social strata. They were originally fishermen, weavers,

woodcutters, gardeners, bird-catchers, beggars, servants, or similar. The

few who were members of the higher castes — the kings, brahmans,

abbots, and university lecturers — all abandoned their privileges so as to

lead the life of the mendicant wandering yogis as “drop-outs”. But their

biographies have nothing in common with the pious Christian legends — they

are violent, erotic, demonic, and grotesque. The American, Keith Dowman, stresses the rebellious character of these

unholy holy men: „Some of these Siddhas

are iconoclasts, dissenters, anti-establishment rebels. [...]

Obsessive caste rules and

regulations in society and religious ritual as an end in itself,

were undermined by the siddhas’ exemplary free

living” (Dowman, 1985, pp. 2). Dowman explicitly refers to their lifestyle as

„spiritual anarchism” which did not allow of any control by

institutionalism (Dowman, 1985, p. 3).

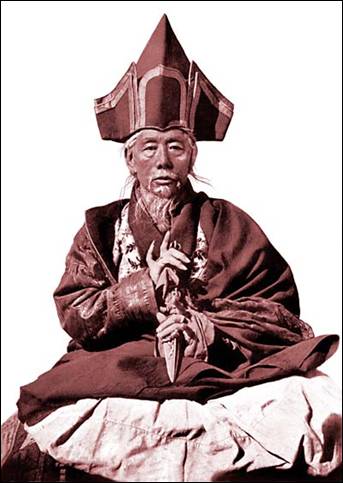

Ling-tsang Gyalpo – a great Nyinma Phurba Master

The relationship with a woman so as to perform the

sexual magic rites with her was at the core of every Siddha’s

life. Whether king or beggar, they all preferred girls from the lower

castes — washer-women, prostitutes, barmaids, dancing girls, or cemetery

witches.

The grand sorcerers’ clothes and external

appearance was also in total contradiction to the image of the Buddhist

monks. They were demonically picturesque. With naked torsos, the Maha Siddhas wore a fur loincloth,

preferably that of a beast of prey. Huge rings hung from their ears and

about their necks swung necklaces of human bone. In contrast to the

ordained bhiksus

(monks) the grand sorcerers never shaved their heads, instead letting their

hair grow into a thick mane which they bound together above their heads in

a knot. Their style more resembled that of the Shivaite

yogis and it was difficult to recognize them as traditional followers of

Gautama Buddha. Many of the Maha Siddhas were

thus equally revered by both the Shivaites and

the Buddhists. From this the Indologist, Ramachandra Rao, concludes

that in the early phase of Tantrism the

membership of a particular religious current was in no way the deciding

criterion for a yogi’s world view, rather, it was the tantric technique

which made them all (independent of their religious affiliation) members of

a single esoteric community (Ramachandra Rao, 1989, p. 42).

The Maha Siddhas

wanted to provoke. Their “demonic nihilism” knew no bounds. They shocked

people with their bizarre appearance, were even disrespectful to kings and

as a matter of principle did the opposite of what one would expect of

either an “ordinary” person or an ordained Mahayana monk. It was a part of their code of honor to publicly

represent their mystic guild through completely unconventional behavior.

Instead of abstinence they enjoyed brandy, rather than peacemakers they

were ruffians. The majority of them took mind-altering drugs. They were dirty

and unkempt. They collected alms in a skull bowl. Some of them proudly fed

themselves with human body parts which lay scattered about the crematoria.

We have reported upon their erotic practices in detail in the first part of

our study, and likewise upon their boundless power fantasies which did not

shy at any crime. Hence, the magic powers (siddhis) were at the top of

their wish list, even if it is repeatedly stressed in the legends that the

“worldly” siddhis

were of only secondary importance. Telepathy, clairvoyance, the ability to

fly, to walk on water, to raise the dead, to kill the living by power of

thought — they constantly performed wonders in their immediate environs so

as to demonstrate their superiority.

But how well can this “spiritual anarchism” of the

Maha Siddhas be reconciled with the

Buddhist conception of state? In his basic character the Siddha is an opponent all state hierarchies and every

form of discipline. All the formalities of life are repugnant to him —

marriage, occupation, position, official accolades and recognition. But

this is only temporarily valid, then once the yogi has attained a state of

enlightenment a wonderful and ordered world arises from this in accordance

with the law of inversion. Thanks to the sexual magic rites of Tantrism the brothel bars have now become divine palaces, nauseating filth has become diamond-clear

purity, stinking excrement shining pieces of gold, horny hetaeras noble

queens, insatiable hate undying love, chaos order, anarchy the absolute state.

The monastic state is, as we shall show in relation to the “history of the

church” in Tibet,

the goal; the “wild life” of the Maha Siddhas in

contrast is just a transitional phase.

For this reason we should not refer to

the tantric yogi not simply as a “spiritual anarchist” as does Keith Dowman, nor as a “villain”. Rather, he is a disciplined

hero of the “good”, who dives into the underworld of erotic love and crime

so as to stage a total inversion there, in that he transforms everything

negative into its positive. He is no libertarian free thinker, but rather

an “agent” of the monastic community who has infiltrated the red-light and

criminal milieu for tactic spiritual reasons. But he does not always see

his task as being to transform the whores, murderers and manslaughterers into saints, rather he likewise

understands it as being to make use of their aggression to protect and

further his own ideas and interests.

The anarchist founding father of

Tibetan Buddhism: Padmasambhava

The most famous of all the great magicians of Tibet is,

even though he is not one of the 84 Maha Siddhas, the Indian, Padmasambhava,

the “Lotus Born”. The Tibetans call him Guru Rinpoche,

“valuable teacher”. He is considered to be not just an emanation of Avalokiteshvara

(like the Dalai Lama) but is himself also, according to the doctrine of the

“Great Fifth”, a previous incarnation of the Tibetan god-king. The reader

should thus always keep in mind that the current Fourteenth Dalai Lama is

accountable for the wild biography of Guru

Rinpoche as his own former life.

Legend tells of his wondrous birth from a lotus

flower — hence his name (padma means ‘lotus’). He

appeared in the form of an eight-year-old boy “without father or mother”,

that is, he gave rise to himself. The Indian king Indrabhuti

discovered him in the middle of a lake, and brought the lotus boy to his

palace and reared him as a son. In the iconography, Padmasambhava

may be encountered in eight different forms of appearance,

behind each of this a legend can be found. His trademark, which

distinguishes him from all other Tibetan “saints”, is an elegant “French”

goatee. He holds the kathanga,

a rod bearing three tiny impaled human heads, as his favorite scepter. His

birthplace in India,

Uddiyana, was famed and notorious for the

wildness of the tantric practices which were cultivated there.

Around 780 C.E. the Tibetan king, Trisong Detsen, fetched Padmasambhava into Tibet. The political intentions

behind this royal summons were clear: the ruler wanted to weaken the power

of the mighty nobles and the caste of the Bon priests via the introduction

of a new religion. Padmasambhava was supposed to

replace at court the Indian scholar, Shantarakshita,

(likewise a Buddhist), who had proved too weak to assert himself against

the recalcitrant aristocracy.

Guru Rinpoche, in

contrast, was already considered to be a tantric superman in Uddiyana. He demanded his own weight in gold bars of

the king as his fee for coming. When he finally stood before Trisong Detsen, the king

demanded that he demonstrate his respect with a bow. Instead of doing so,

Guru Rinpoche sprayed lightning from his

fingertips, so that it was the king who sank to his knees and recognized

the magician as the appropriate ally with whom to combat the Bon priests,

likewise skilled in magic things. The guru was thus bitterly hated by these

and by the nobles, even the king’s ministers

treated him with the greatest hostility imaginable.

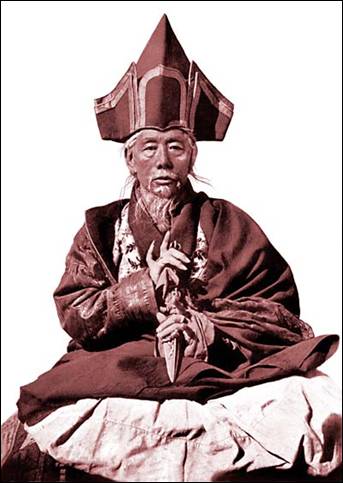

Statue of Padmasambhava

The saga has made Padmasambhava

the founding father of Tibetan Buddhism. His life story is a fantastic

collection of miracles which made him so popular among the people that he

soon enjoyed a greater reverence than the historical Buddha, whose life

appeared sober and pale in comparison. Reports about Guru Rinpoche and his writings are drawn primarily from the termas

(treasures) already mentioned above, which, it is claimed, he himself hid

so that they would come to light centuries later.

From a very young age the boy already stood out

because of his abnormal and violent nature. He killed a sleeping baby by

throwing a stone at it and justified this deed with the pretense that the

child would have become a malignant magician who would have harmed many

people in his later life. Apart from his royal adoptive father, Indrabhuti, no-one accepted this argument, and several

people attempted to bring him to justice. At the urgings of a minister he

was first confined to a palace by soldiers. Shortly afterward the guru

appeared upon the roof of the building, naked except for a “sixfold bone ornament”, and with a vajra and a trident in his

hands. The people gathered rapidly to delight in the odd spectacle, among

them one of the hostile ministers with his wife and son. Suddenly and

without warning Padmasambhava’s vajra

penetrated the brain of the boy and the trident speared through the heart

of the mother fatally wounding both of them.

The pot boiled over at this additional

double murder and the entire court now demanded that the wrongdoer be

impaled. Yet once again he succeeded in proving that the murder victims had

earned their violent demise as the just punishment for their misdeeds in

earlier lives. It was decided to refrain from the death penalty and to damn

Padmasambhava instead. Thereupon a troupe of

dancing dakinis appeared in the skies leading a

miraculous horse by the halter. Guru Rinpoche

mounted it and vanished into thin air. Acts of violence were to continue to

characterize his future life.

As much as he was a master of tantric erotic love,

he decisively rejected the institution of marriage. When Indrabhuti wanted to find him a wife, he answered by

saying that women were like wild animals without minds and that they vainly

believed themselves to be goddesses. There were, however, exceptions, as

well hidden as a needle in a haystack, and if he would have to marry then

he should be brought such an exception. After many unsuccessful

presentations, Bhasadhara was finally found. With

her he began his tantric practices, so that “the mountains shook and the

gales blew”.

The marriage did not last long. Like the

historical Buddha, Guru Rinpoche turned his back

on the entertaining palace life of his adoptive father and chose as his

favorite place to stay the crematoria of India. He was in the habit of

meditating there, and there he held his constant rendezvous with

terrible-looking witches (dakinis). One document

reports how he dressed in the clothes of dead and fed upon their

decomposing flesh (Herrmann-Pfand, 1992, p. 195).

He is supposed to have visited a total of eight cemeteries in order to

there and then fight out a magical initiation battle with the relevant

officiating dakinis.

His most spectacular encounter was definitely the

meeting with Guhya Jnana,

the chief of the terror goddesses, one of the appearances of Vajrayogini.

She lived in a castle made of human skulls. When Padmasambhava

reached the gates he was unable to enter the building, despite his magic

powers. He instructed a servant to inform her mistress of his visit. When

she returned without having achieved anything he tried once more with all

manner of magic to gain entry. The girl laughed at him, took a crystal

knife and slit open her torso with it. The endless retinue of all the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas appeared within her insides.

“I am just a servant”, she said. Only now was Padmasambhava

admitted.

Guhya

Inana sat upon her throne. In her hands she held a

double-ended drum and a skull bowl and was surrounded by 32 servant girls.

The yogi bowed down with great respect and said, “Just as all Buddhas through the ages had their gurus, so I ask you

to be my teacher and to take me on as your pupil” (Govinda,

1984, p. 226). Thereupon she assembled the whole pantheon of gods within

her breast, transformed the petitioner into a seed syllable and swallowed

him. Whilst the syllable lay upon her lips she gave him the sacrament of Amitabha,

whilst he rested in her stomach he was initiated into the secrets of Avalokiteshvara.

After leaving her lotus (i.e., vagina) he received the sacraments of the

body, the speech, and the spirit. Only now had he attained his immortal vajra body.

This scene also grants the feminine force an

outstanding status within the initiation process. But there are several

versions of the story. In another account it is Padmasambhava

who dissolves Vajrayogini

within his heart. Jeffrey Hopkins even describes a tantra

technique in which the pupil imagines himself to be the goddess so as to

then be absorbed by his teacher who visualizes himself as Guru Rinpoche

(Hopkins, 1982, p. 180).

Without doubt, Padmasambhava’s

relationship with Yeshe Tshogyal, the karma

mudra given to him by Indrabhuti,

and with Princess Mandavara, the reincarnation of

a dakini, display a rare tolerance. Thus

within the tradition both yoginis were able to

preserve a certain individuality and personality over the course of

centuries — a rare exception in the history of Vajrayana. For this reason it

could be believed that Padmasambhava had shown a

revolutionary attitude towards the woman, especially since the statement

often quoted here in the West is from him: “The basis for realizing

enlightenment is a human body. Male or female — there is no great

difference. But if she develops the mind bent on enlightenment, a woman's

body is better” (Gross, 1993, p. 79).

But how can this comment,

which is taken from a terma from the 18th century (!), be

reconciled with the following statement by the guru, which he is supposed

to have offered in answer to Yeshe Tshogyal’s question about the suitability of women for

the tantric rituals? „Your faith is mere platitude, your devotion

insincere, but your greed and jealousy are strong. Your trust and

generosity are weak, yet your disrespect and doubt are huge. Your

compassion and intelligence are weak, but your bragging and self-esteem are

great. Your devotion and perseverance are weak, but you are skilled at

misguiding and distorting Your pure perception and courage is small”

(Binder-Schmidt, 1994 p. 56).

Yet this comment is quite harmless! The “demonic” Guru Rinpoche

also exists — the aggressive butcher of people and serial rapist. There is

for instance a story about him in circulation in which he killed a Tibetan

king and impregnated his 900 wives so as to produce children who were

devoted to the Buddhist teaching. In another episode from his early life he

was attacked out of the blue by dakinis and male dakas. The story reports that “he [then] kills the men

and possesses the women” (R. Paul, 1982, p. 163). Robert A. Paul thus sees

in Padmasambhava an intransigent, active,

phallic, and sexist archetype whom he contrasts

with Avalokiteshvara,

the mild, asexual, feminized, and transcendent counterpole.

Both typologies, Paul claims, determine the dynamic of Tibetan history and

are united within the person of the Dalai Lama (R. Paul, 1982, p. 87).

Many of the anecdotes about Guru Rinpoche which are in

circulation also depict him as a boastful superman. He paid for his beer in

a tavern by holding the sun still for two days for the female barkeeper.

This earned him not just the reputation of a sun-controller but also the

saga that he had invented beer in an earlier incarnation. His connection to

the solar cults is also vouched for by other anecdotes. For instance, one

day he assumed the shape of the sun bird, the garuda, and conquered the lu, the feminine (!) water spirits. Lightning magic

remained one of his preferred techniques, and he made no rare use of it. An

additional specialty was to appear in a sea of flames, which was not

difficult for him as an emanation of the “fire god”, Avalokiteshvara. His siddhis

(magic powers) were thought to be unlimited; he flew through the air, spoke

all languages, knew every magic battle technique, and could assume any

shape he chose. Nonetheless, all these magical techniques were not

sufficient for him to remain the spiritual advisor of Trisong

Detsen for long. The Bon priests and the king’s

wife (Tse Pongza) were

too strong and Guru Rinpoche had to leave the

court. Yet this was not the end of his career. He moved north in order to

do battle with the unbridled demons of the Land of Snows.

The rebellious spirits, usually local earth deities, constantly blocked his

path. Yet without exception all the “enemies of the teaching” were defeated

by his magic powers. The undertaking soon took on the form of a triumphal

procession.

It was Guru Rinpoche’s

unique style to never destroy the opponents he defeated but rather to

demand of them a threefold gesture of submission: 1. the demons had to

symbolically offer up to him their life force or “heart blood”; 2. they had

to swear an oath of loyalty; and 3. they had to commit themselves to

fighting for instead of against the Buddhist teachings in future. If these

conditions were met then they did not need to abandon their aggressive,

bloodthirsty, and extremely destructive ways. In contrast, they were not

freed from their murderous fighting spirit and their terrifying ugliness

but instead from then on served Tantric Buddhism as it terrible protective

deities, who were all the more holy the more cruelly they behaved. The

Tibetan Buddhist pantheon was thus gradually filled out with all imaginable

misshapen figures, whose insanity, atrocities, and misanthropy were

boundless. Among them could be found vampires, cannibals, executioners,

ghouls (horrifying ghosts), and sadists. Guru Rinpoche

and his later incarnations, the Dalai Lamas, were and still are considered

to be the undisputed masters of this cabinet of horrors, who they regally

command from their lotus throne.

His victory over the daemonic powers was sealed by

the construction of a three-dimensional mandala,

the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet. Samye symbolized nothing less

than a microcosmic model of the tantric world system, with Mount Meru at

its center. The inaugurating ceremony conducted by Padmasambhava

was preceded by the banishment of all venomous devils. Then the earth

goddess, Srinmo, was nailed down, in that Guru Rinpoche drove his phurba (ritual dagger) into

the ground with a ceremonial gesture. Among those present at this ritual

were 50 beautifully adorned girls and boys with vases filled with valuable

substances. Durong the subsequent construction

works the rebellious spirits repeatedly tried to prevent the completion of

the temple and at night tore down what had been achieved during the day.

But here too, the guru understood how to tame the nightly demons and then

make construction workers of them.

In the holiest of holies of Samye

there could be found a statue of Avalokiteshvara which

was said to have arisen of itself. Apart from this, the monastery had

something of an eerie and gloomy air about it. The saga tells of how once a

year Tibet’s

terror gods assembled on the roofs of the monastery for a cannibalistic

feast and a game of dice in which the stakes were human souls. On these

days all the oracle priests of the Land of Snows

were said to have fallen into a trance as if under the instruction of a

higher power. Because of the microcosmic significance of Samye, its protective god is the Red Tsiu, a mighty force in the

pandemonium of the highlands. “He possesses red locks,

his body is surrounded by a glory of fire. Shooting stars fly from his eyes

and a great hail of blood falls from his mouth. He gnashes his teeth. ...

He winds a red noose about the body of an enemy at the same time as he

thrusts a lance into the heart of another” (Nebesky-Wojkowitz,

1955, p. 224).

A puzzling red-brown leather mask also hung in the

temple, which showed the face of a three-eyed wrathful demon. Legend tells

that it was made from clotted human blood and sometimes becomes alive to the horror of

all. Alongside the sacred room of the Red

Tsiu lay a small, ill-lit chamber. If a

person died, said the monks, then his soul would have to slip through a

narrow hole into this room and would be cut to pieces there upon a chopping

block. Of a night the cries and groans of the maltreated souls could be

heard and a revolting stench of blood spread through the whole building.

The block was replaced every year since it had been worn away by the many

blows.

Guru Rinpoche, the former incarnation of the Dalai

Lama, was a explosive mixture of strict ascetic

and sorcerer, apostle and adventurer, monk and vagabond, founder of a

culture and criminal, mystic and eroticist, lawmaker and mountebank,

politician and exorcist. He had such success because he resolved the

tension between civilization and wildness, divinity and the daemonic within

his own person. For, according to tantric logic, he could only defeat the

demons by himself becoming a demon. For this reason Fokke

Sierksma also characterizes him as an uninhibited

usurper: “He was a conqueror, obsessed by lust of power and concupiscence,

only this conqueror did not choose the way of physical, but that of

spiritual violence, in accordance with the Indian tradition that the Yogin's concentration of energy subdues matter, the

world and gods” (Sierksma, 1966, p. 111).

The orthodox Gelugpas

also pull the arch magician to pieces in general. For example, one document

accuses him of having devoted himself to the pursuit of women of a night

clothed in black, and to drink of a day, and to have described this

decadent practice as “the sacrifice of the ten days” (Hoffmann, 1956, p.

55).

It was different with the Fifth Dalai Lama — for

him Guru Rinpoche was the force which tamed the

wilds of the Land

of Snows with his

magic arts, as had no other before him and none who came after. As magic

was likewise for the “Great Fifth” the preferred style of weapon, he could

justifiably call upon Padmasambhava as his

predecessor and master. The various guises of the guru which appeared

before the ruler of the Potala in his visions are

thus also numerous and of great intensity. In them Padmasambhava

touched his royal pupil upon the forehead a number of times with a jewel

and thus transferred his power to him. Guru Rinpoche

became the “house prophet” of the “Great Fifth” — he advised the hierarch,

foretold the future for him, and intervened in the practical politics from

beyond, which fundamentally transformed the history of Tibet (through the

establishment of the Buddhist state) almost 900 years after his death.

The “Emperor” Songtsen Gampo and the “Magician-Priest” Padmasambhava,

the principal early heroes of the Land of Snows,

carried within them the germ of all the future events which would determine

the fate of the Tibetans. Centuries after their earthly existence, both

characters were welded together into the towering figure of the Fifth Dalai

Lama. The one represented worldly power, the other the spiritual. As an

incarnation of both the one and the other, the Dalai Lama was also entitled

and able to exercise both forms of power. Just how close a relationship he

brought the two into is revealed by one of his visions in which Guru Rinpoche and King Songtsen Gampo swapped their appearances with lightning speed

and thus became a single person. A consequence of

the Dalai Lama’s strong identification with the arch-magician was that his

chief yogini, Yeshe Tshogyal, also appeared all the more often in his envisionings. She became the preferred inana mudra of

the “Great Fifth”.

Under the rule of Trisong

Detsen (who fetched Padmasambhava

into Tibet)

the famous Council of Lhasa also took place. The king ordered the staging

of a large-scale debate between two Buddhist schools of opinion: the

teachings of the Indian, Kamalashila, which said

that the way to enlightenment was a graded progression and the Chinese

position, which demanded the immediate, spontaneous achievement of

enlightenment, which suddenly and unexpectedly unfolded in its full

dimensions. The representative of the spontaneity doctrine was Hoshang Mahoyen, a master of

Chinese Chan Buddhism. In Lhasa

the Indian doctrine of stages was at the end of a two-year debate

victorious. Hoshang is said to have been banished

from the land and some of his followers were killed by the disciples of Kamalashila. But the Chinese position has never

completely disappeared from Tibetan cultural life and is again gaining

respectability. It is quite rightly compared to the so-called Dzogchen teaching, which also believes an immediate act

of enlightenment is possible and which is currently especially popular in

the West. For example, the important abbot, Sakya

Pandita, attacked the Dzogchen

practices because they were a latter-day form of the Chinese doctrine which

had been refuted at the Council of Lhasa. In contrast the unorthodox Nyingmapa had no problem with the “Chinese

way”. These days the Tibetan lama, Norbu Rinpoche, who lives in Italy, appeals explicitly to Hoshang.

Of its nature, the Dzogchen

teaching stands directly opposed to state Buddhism. It dissolves all forms

at once and it would not be exaggerating if we were to describe it as

“spiritual anarchism”. The political genius of the Fifth Dalai Lama, who

knew that a Buddhocracy is only sustainable if it

can integrate and control the anarchic elements, made constant use of the Dzogchen practice (Samuel, 1993, p. 464). Likewise the

current Fourteenth Dalai Lama is said to have been initiated into this

discipline, at any rate he counts Dzogchen

masters among his most high ranking spiritual intimates.

It is also noteworthy that in feminist circles the

famous Council of Lhasa is evaluated as the confrontation between a

fundamentally masculine (Indian) and a feminine (Chinese) current within

Tibetan Buddhism (Chayet, 1993, pp. 322-323).

From anarchy to the discipline of the order: The Tilopa lineage

The reason the Maha Siddha Tilopa

(10th century) is worthy of our special attention is because he and his

pupil Naropa are the sole historical individuals

from the early history of the Kalachakra Tantra who count among the founding fathers of

several Tibetan schools and because Tilopa’s life

is exemplary of that of the other 83 “grand sorcerers”.

According to legend, the Indian master is said to

have reached the wonderland of Shambhala and

received the time doctrines from the reigning Kalki

there. After returning to India,

in the year 966 he posted the symbol of the dasakaro vasi (the “Power of Ten”) on the

entrance gates of the monastic university

of Nalanda

and appended the following lines, already quoted above: “He, that does not

know the chief first Buddha (Adi-Buddha),

knows not the circle of time (Kalachakra).

He, that does not know the circle of time, knows not the exact enumeration

of the divine attributes. He that does not know the exact enumeration of

the divine attributes, knows not the supreme

intelligence. He, that does not know the supreme intelligence, knows not

the tantrica principles. He, that does not know

the tantrica principles, and all such, are

wanderers in the orb transmigratos,

and are out of the way of the supreme triumphator.

Therefore Adi-Buddha must be taught by every true

Lama, and every true disciple who aspires to

liberation must hear them” (Körös, 1984, pp.

21-22).

While he was still a very young child, a dakini bearing the 32 signs of ugliness appeared to Tilopa and proclaimed his future career as a Maha Siddha to

the boy in his cradle. From now on this witch, who was none other than Vajrayogini,

became the teacher of the guru-to-be and inducted him step by step in the

knowledge of enlightenment. Once she appeared to him in the form of a

prostitute and employed him as a servant. One of his duties was to pound

sesame seeds (tila)

through which he earned his name. As a reward for the services he

performed, Vajrayogini

made him the leader of a ganachakra.

Tilopa always proved to be the androgynous sovereign of

the gender roles. Hence he one day let the sun and the moon plummet from

heaven and rode over them upon a lion, that is, he destroyed the masculine

and feminine energy flows and controlled them with the force of Rahu the darkener. At another point, in

order to demonstrate his control over the gender polarity, he was presented

as the murderer of a human couple “who the beat in the skulls of the man

and the woman” (Grünwedel, 1933, p. 72).

Another dramatic scene tells of how dakinis angrily barred his way when he wanted to enter

the palace of their head sorceress and cried out in shrill voices: “We are

flesh-eating dakinis. We enjoy flesh and are

greedy for blood. We will devour your flesh, drink of your blood, and

transform your bones into dust and ashes” (Herrmann-Pfand,

1992, p. 207) .Tilopa defeated them with the

gesture of fearlessness, a furious bellow and a penetrating stare. The

witches collapsed in a faint and spat blood. On his way to the queen he

encountered further female monsters which he hunted down in the same

manner. Finally, in the interior of the palace he met Inana Dakini, the custodian of tantric

knowledge, surrounded by a great retinue. But he did not bow down before

her throne, and sank instead into a meditative stance. All present were

outraged and barked at him in anger that before him stood the “Mother of

all Buddhas”. According to one version — which is

recounted by Alexandra David-Neel — Tilopa now

roused himself from his contemplation, and, approaching the queen with a

steady gait, stripped her of her clothes jewelry and demonstrated his male

superiority by raping her before the assembled gaze of her entire court

(Hoffmann, 1956, p. 149).

Tilopa’s character first becomes three dimensional when we

examine his relationship with his pupil, Naropa.

The latter first saw the light of the world in the year of the masculine

fire dragon as the son of a king and queen. Later he at first refused to

marry, but then did however succumb to the will of his parents. The

marriage did not last long and was soon dissolved. Naropa

offered the following reason: “Since the sins of a woman are endless, in

the face of the swamp mud of deceptive poison my spirit would take on the

nature of a bull, and hence I will become a monk” (Grünwedel,

1933, p. 54). His young spouse agreed to the divorce and accepted all the

blame: “He is right!”, she said to his parents, “I

have endless sins, I am absolutely without merit ... For this reason and on

these grounds it is appropriate to put an end to [the union of] us two” (Grünwedel, 1933, p. 54). Afterwards Naropa

was ordained as a monk and went on to become the abbot of what was at the

time the most important of the Buddhist monastic universities, Nalanda.

Nevertheless, one day the ecclesiastical dignitary

renounced his clerical privileges just as he had done with his royal ones

and roamed the land as a beggar in search of his teacher, Tilopa. He had learned of the latter’s existence from

the dakini with the 32 markings of ugliness (Vajrayogini).

While he was reading the holy texts in Nalanda,

she cast a threatening shadow across his books. She laughed at him

derisively because he believed he could understand the meaning of the tantras by reading them.

After Naropa had with

much trouble located his master, a grotesque scene, peerless even in the

tantric literature, was played out. Tilopa fooled

his pupil with twelve horrific apparitions before finally initiating him.

On the first occasion he appeared as a foul-smelling, leprous woman. He

then burnt fish that were still alive over a fire in order to eat them

afterwards. At a cemetery he slit open the belly of a living person and

washed it out with dirty water. In the next scene the master had skewered

his own father with a stake and was in the process of killing his mother

held captive in the cellar. On another occasion Naropa

had to beat his penis with a stone until it spurted blood. At another time Tilopa required of him that he vivisect himself.

In order to reveal the world to be an illusion,

the tantra master had his pupil commit one crime

after another and presented himself as a dastardly criminal. Naropa passed every test and became one of the finest

experts and commentators on the Kalachakra Tantra.

One of his many pupils was the Tibetan, Marpa (1012-1097). Naropa

initiated him into the secret tantric teachings. After further initiations

from burial ground dakinis, whom Marpa defeated with the help of Tilopa

who appeared from the beyond, and after encountering the strange yogi, Kukkuri ("dog ascetic”), he returned from India to

his home country. He brought several tantra texts

back with him and translated these into the national language, giving him

his epithet of the “translator”. In Tibet he married several women,

had many sons and led a household. He is said to have performed the tantric

rites with his head wife, Dagmema. In contrast to

the yoginis of the legendary Maha Siddhas,

Dagmema displays very individualized traits and

thus forms a much-cited exception among the ranks of female Tibetan

figures. She was sincere, clever, shrewd, self-controlled and industrious.

Besides this she had independent of her man her own possessions. She cared

for the family, worked the fields, supervised the livestock and fought with

the neighbors. In a word, she closely resembled a normal housewife in the

best sense.

A monastic interpretation of Marpa’s

“ordinary” life circumstances reveals, however, how profoundly the

anarchist dimension dominated the consciousness of the yogis at that time: Marpa’s “normality” was not considered a good deed of

his because it counted as moral in the dominant social rules of the time,

but rather, in contrast, because he had taken the most difficult of all

exercises upon himself in that he realized his enlightenment in the so

despised “normality”. “People of the highest capacity can and should

practice like that” (Chökyi, 1989, p. 143).

Effectively this says that family life is a far greater hindrance to the

spiritual development of a tantra master than a

crematorium. This is what Marpa’s pupil, Milarepa, also wanted to indicate when he rejected

marriage for himself with the following words: “Marpa

had married for the purpose of serving others, but ... if I presumed to imitate him without being

endowed with his purity of purpose and his spiritual power, it would be the

hare's emulation of the lion’s leap, which would surely end in my being

precipitated into the chasm of destruction” (R. Paul, 1982, p. 234)

Marpa’s pragmatic personality, especially his almost

egalitarian relationship with his wife, is unique in the history of Tibetan

monasticism. It has not been ruled out that he conceived of a reformed

Buddhism, in which the sex roles were supposed to be balanced out and which

strove towards the normality of family relationships. Hence, he also wanted

to make his successor his son, who lost his life in an accident, however.

For this reason he handed his knowledge on to Milarepa

(1052–1135), who was supposed to continue the classic androcentric

lineage of the Maha Siddhas.

Milarepa’s family were

maliciously cheated by relatives when he was in his youth. In order to

avenge himself, he became trained as a black magician and undertook several

deadly acts of revenge against his enemies. According to legend his mother

is supposed to have spurred him on here. In the face of the unhappiness he

had caused, he saw the error of his ways and sought refuge in the Buddhist

teachings. After a lengthy hesitation, Marpa took

him on as a pupil and increased his strictness towards him to the point of

brutality so that Milarepa could work off his bad

karma through his own suffering. Time and again the pupil had to build a

house which his teacher repeatedly tore down. After Milarepa

subsequently meditated for seven nights upon the bones of his dead mother

(!), he attained enlightenment. In his poems he does not just celebrate the

gods, but also the beauty of nature. This “natural” talent and inclination

has earned him many admirers up until the present day.

Like his teacher, Marpa,

Milarepa is primarily revered for his humanity, a

rare quality in the history of Vajrayana. There is something so realistic about Marpa’s arbitrariness and the despair of his pupil that

they move many believers in Buddhism more than the phantasmagoric cemetery

scenes we are accustomed to from the Maha Siddhas

and Padmasambhava. For this reason the ill

treatment of Milarepa by his guru counts among

the best-known scenes of Tibetan hagiography. Yet after his initiation

events also became fantastic in his case. He transformed himself into all

manner of animals, defeated a powerful Bon magician and thus conquered the mountain of Kailash.

But the death of this superhuman is once again just as human as that of the

Buddha Shakyamuni. He died after drinking

poisoned milk given him by an envious person. The historical Buddha passed

away at the age of 80 after consuming poisoned pork.

Milarepa’s sexual life oscillated between ascetic

abstinence and tantric practices. There are several misogynous poems by

him. When the residents of a village offered the poet a beautiful girl as

his bride, he sang the following song:

At first, the lady is like a heavenly angel;

The more you look at her, the more you want to gaze.

Middle-aged, she becomes a demon with a corpse’s eyes;

You say one word to her and she shouts back two.

She pulls your hair and hits your knee.

You strike her with your staff, but back she throws a ladle….

I keep away from women to avoid fights and quarrels.

For the young bride you mentioned, I have no appetite.

(Stevens, 1990, p.

75)

The yogi constantly warned of the destructive

power of women, and attacked them as troublemakers, as the source of all

suffering. Like all the prominent followers of Buddha he was exposed to

sexual temptations a number of times. Once a demoness

caused a huge vagina to appear before him. Milarepa

inserted a phallus-like stone into it and thus exorcised the magic. He

conducted a ganachakra

with the beautiful Tserinma and her four sisters.

Milarepa’s pupil, Gampopa

(1079–1153), drew the wild and anarchic phase of the Tilopa

lineage to a close. This man with a clear head who had previously practiced

as a doctor and became a monk because of a tragic love affair in which his

young wife had died, brought with him sufficient organizational talent to

overcome the antisocial traits of his predecessors. Before he met Milarepa, he was initiated into the Kadampa

order, an organization which could be traced back to the Indian scholar, Atisha, and already had an

statist character. As he wanted to leave them to take the yogi poet (Milarepa) as his teacher, his brethren from the order

asked Gampopa ,: “Aren’t our teachings enough?” When he nonetheless

insisted, they said to him: “Go, but [do] not abandon our habit.” (Snellgrove, 1987, vol. 2, p. 494). Gampopa

abided by this warning, but likewise he took to heart the following

critical statement by Milarepa: “The Kadampa have teachings, but practical teachings they

have not. The Tibetans, being possessed by evil spirits, would not allow

the Noble Lord (Atisha) to preach the Mystic

Doctrine. Had they done so, Tibet

would have been filled with saints by this time” (Bell, 1994, p. 93).

The tension between the rigidity of the monastic

state and the anarchy of the Maha Siddhas is

well illustrated by these two comments. If we further follow the history of

Tibetan Buddhism, we can see that Gampopa abided

more closely to the rules of his original order and only let himself be temporarily seduced by the wild life of the

“mountain ascetic”, Milarepa. In the long term he

is thus to be regarded as a conqueror of the anarchic currents. Together

with one of his pupils he founded the Kagyupa

order.

The actual chief figure in the establishment of

the Tibetan monastic state was the above-mentioned Atisha

(982–1054). The son of a prince from Bengal

already had a marriage and nine children behind him before he decided to

seek refuge in the sangha.

Among others, Naropa was one of his teachers. In

the year 1032, after several requests from the king of Guge

(southern Tibet),

he went to the Land

of Snows in order to

reform Buddhism there. In 1050, Atisha organized

a council in which Indians also participated alongside many Tibetan monks.

The chief topic of this meeting was the “Re-establishment of religion in Tibet”.

Under Tantrism the

country had declined into depravity. Crimes, murders, orgies, black magic,

and lack of discipline were no longer rare in the sangha (monastic community). Atisha opposed

this with his well-organized and disciplined monastic model, his moral

rectitude and his high standard of ethics. A pure lifestyle and true

orderly discipline were now required. The rules of celibacy applied once

more. An orthodoxy was established, but Tantrism was in no sense abolished, but rather

subjected to maximum strictness and control. Atisha

introduced a new time-keeping system into Tibet which was based upon the

calendar of the Kalachakra Tantra,

through which this work became exceptionally highly regarded.

Admittedly there is a story which tells of how a

wild dakini initiated him in a cemetery, and he

also studied for three years at the notorious Uddiyana

from whence Padmasambhava came, but his lifestyle

was from the outset clear and exact, clean and disciplined, temperate and

strict. This is especially apparent in his choice of female yiddam (divine appearance), Tara. Atisha

bought the cult of the Buddhist “Madonna” to Tibet with him. One could say

he carried out a “Marianization” of Tantric

Buddhism. Tara

was essentially quite distinct from the other female deities in her purity,

mercifulness, and her relative asexuality. She is the “spirit woman” who

also played such a significant role in the reform of other androcentric churches, as we can see from the example

provided by the history of the Papacy.

At the direction of his teacher, Atisha’s pupil Bromston

founded community of Kadampas whom we have

already mentioned above, a strict clerical organization which later became

an example for all the orders of the Land of Snows

including the Nyingmapas and the remainder of the

pre-Buddhist Bonpos. But in particular it paved

the way for the victory march of the Gelugpas.

This order saw itself as the actual executors of Atisha’s

plans. With it the nationalization of Tibetan monasticism began. This was

to reach its historical high point

in the institutionalization of the office of the Dalai Lama.

The pre-planned counterworld to the clerical

bureaucracy: Holy fools

The archetype of the anarchist Maha Siddha is primarily an Indian

phenomenon. Later in Tibet

it is replaced by that of the “holy fools”, that is, of the roaming yogis

with an unconventional lifestyle. While the “grand sorcerers” of India still

enjoyed supreme spiritual authority, before which abbots and kings had to

bow, the holy fools only acted as a social pressure valve. Everything wild,

anarchic, unbridled, and oppositional in Tibetan society could be diverted

through such individuals, so that the repressive pressure of the Buddhocracy did not too much gain the upper hand and

incite real and dangerous revolts. The role of the holy fools was thus, in

contrast to that of the Maha Siddhas,

planned in advance and arranged by the state and hence a part of the

absolutist Buddhocracy. John Ardussi

and Lawrence Epstein have encapsulated the principal characteristics of

this figure in six points:

- A general rejection of the usual

social patterns of behavior especially the rules of the clerical

establishment.

- A penchant for bizarre clothing.

- A cultivated non-observance of

politeness, above all with regard to respect for social status.

- A publicly proclaimed contempt for

scholasticism, in particular a mockery of religious study through

books alone.

- The use of popular poetic forms,

of mimicry, song, and stories as a means of preaching.

- The frequent employment of obscene

insinuations (Ardussi and Epstein, 1978, pp.

332–333).

These six characteristics doe

not involve a true anarchist rejection of state Buddhism. At best, the holy

fools made fun of the clerical authorities, but they never attacked these

as such.

The roaming yogis primarily became famous for

their completely free and uninhibited sexual morals and thus formed a

safety valve for thousands of abstinent monks living in celibacy, who were

subjected to extreme sexual pressure by the tantric symbolism. What was

forbidden for the ordained monastery inmates was lived out to the full by

the vagabond “crazy monks”: They praised the size of their phallus, boasted

about the number of women they had possessed, and drifted from village to

village as sacred Casanovas. Drukpa Kunley (1455–1529) was the most famous of them. H sings

his own praises in a lewd little song:

People say Drukpa Kunley is utterly mad

In Madness all sensory forms are the Path!

People say Drukpa Kunley’s organ is immense

His member brings joy to the hearts of young girls!

(quoted by Stevens,

1990, p. 77)

Kunley’s

biography begins with him lying in bed with his mother and trying to seduce

her. As, after great resistance, she was prepared to surrender to her son’s

will, he, a master of tantric semen retention, suddenly springs up and

leaves her. Amazingly, this uninhibited outsider was a member of the strict

Kadampa order — this too can only be understood

once we have recognized the role of the fool as a paradoxical instrument of

control.

An anarchist erotic: The Sixth Dalai Lama

At first glance it may appear absurd to include the

figure of the Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso (1683-1706), in a chapter on “Anarchism and Buddhocracy”, yet we do have our reasons for doing so.

Opinions are divided about this individual: for those who are sympathetic

towards him, he counts as a rebel, a popular hero, a poète maudit, a Bohemian, a romantic on

the divine throne, an affectionate eroticist, as clever and attractive. The

others, who view him with disgust, hold him to be a heretic and besmircher of the Lion Throne, reckless and depraved.

Both groups nonetheless describe him as extremely apolitical.

He became well-known and notorious above all

through his love poems, which he dedicated to several attractive

inhabitants of Lhasa.

Their self ironic touch, melancholy and subtle mockery of the bureaucratic Lamaist state have earned them a place in the

literature of the world. For example, the following five-line poem combines

all three elements:

When I’m at the Potala Monastery

They call me the Learned

Ocean of Pure Song;

When I sport in the

town,

I’am known as the Handsome Rogue who loves Sex!.

(quoted by Stevens,

1990, p. 78)

The young “poet prince” stood in impotent

opposition to the reigning regent, Sangye Gyatso (1653-1705), who claimed the power of state for

himself alone. The relationship between the two does not lack a certain

piquancy if, following Helmut Hoffmann, one assumes that the regent was the

biological son of the “Great Fifth” and thus stood opposed to the Sixth Dalai

Lama as the youthful incarnation of his own father. Nevertheless, this did

not prevent him from treating the young “god-king” as a marionette in his

power play with the Chinese and Mongolians. When the Dalai Lama expressed

own claim to authority, his “sinful activities “ were

suddenly found to be so offensive that his abdication was demanded.

Oddly enough the sixth Kundun accepted this without

great pause, and in the year 1702 decided to hand his spiritual office over

to the Panchen Lama; his worldly authority,

however, which he de jure but

never de facto exercised, he

wanted to retain. This plan did not come to fruition, however. A

congregation of priests determined that the spirit of Avalokiteshvara had left him

and appointed an opposing candidate. In the general political confusion

which now spread through the country, in which the regent, Sangye Gyatso, lost his life,

the 24-year-old Sixth Dalai Lama was also murdered. Behind the deed lay a

conspiracy between the Chinese Emperor and the Mongolian Prince, Lhabsang Khan. Nonetheless, according to a widely

distributed legend, the “god-king” was not killed but lived on anonymously

as a beggar and pilgrim and was said to have still appeared in the country

under his subsequent incarnation, the Seventh Dalai Lama.

Western historians usually see a tragic aesthete

in the figure of the poet prince, who with his erotic lines agreeably broke

through the merciless power play of the great lamas. We are not entirely

convinced by this view. In contrast, in our view Tsangyang

Gyatso was all but dying to attain and exercise

worldly power in Tibet,

as was indeed his right. It is just that to this end he did not make use of

the usual political means, believing instead that he could achieve his goal

by practicing sexual magic rites. He firmly believed in what stood in the

holy texts of the tantras; he was convinced that

could gain power over the state via “sexual anarchy”.

The most important piece

of information which identifies him as a practicing Tantric is the

much-quoted saying of his: „Although I sleep with a woman every night, I

never lose a drop of semen” (quoted by Stevens, 1990, p. 78). With this statement he not only

justified his scandalous relationships with women; he also wanted to

express the fact that his love life was in the service of his high office

as supreme vajra

master. One story tells of how, in the presence of his court, he publicly

urinated from the platform roof of the Potala in

a long arc and was able to draw his urine back into his penis. Through this

performance he wanted to display the evidence that in his much-reproached

love life he behaved correctly and in accordance with the tantric codex,

indeed that he had even mastered the difficult draw-back technique (the Vajroli method) needed in order to appropriate

the female seed (Schulemann, 1958, p. 284). It is

not very difficult to see from the following poem that his rendezvous were

for him about the absorption of the male-female fluids.

Glacier-water (from) 'Pure Crystal

Mountain'

Dew-drops from (the herb) 'Thunderbolt of Demonic Serpent'

(Enriched by) the balm of tonic elixir;

(Let) the Wisdom-Enchantress(es)

be the liquor-girl(s):

If you drink with a pure commitment

Infernal damnation need not be tasted.

(see Sorensen, 1990,

p. 113)

Other verses of his also make unmistakable

references to sexual magic practices (Sorensen, 1990, p. 100). He himself

wrote several texts which primarily concern the terror deity, Hayagriva.

From a tantric point of view his “seriousness” would also not have been

reduced by his getting involved with barmaids and prostitutes, but rather

in contrast, it would have been all but proven, because according to the

law of inversion, of course, the highest arises from the most

lowly. He is behaving totally in the spirit of the Indian Maha Siddhas when he sings:

If the bar-girl does not falter,

The beer will flow on and on.

This maiden is my refuge,

and this place my haven.

(Stevens, 1990, p.

78, 79)

He ordered the construction of a magnificently

decorated room within the Potala probably for the

performance of his tantric rites and which he cleverly called the “snake

house”. In his external appearance as well, the “god-king” was a Vajrayana

eccentric who evoked the long-gone magical era of the great Siddhas. Like them, he let his hair grow long and tied

it in a knot. Heavy earrings adorned his lobes, on

every finger he wore a valuable ring. But he did not run around naked like

many of his role-models. In contrast, he loved to dress magnificently. His

brocade and silk clothing were admired by Lhasa’s jeunesse dorée with whom

he celebrated his parties.

But these

were all just externals. Alexandra David-Neel’s suspicion is obviously spot on when she assumes: “Tsangyang

Gyatso was apparently initiated into methods

which in our terms allow or even encourage a life of lust and which also

really signified dissipation for anyone not initiated into this strange

schooling” (Hoffmann, 1956, 178, 179).

We know that in the tantric rituals the individual

karma mudras

(wisdom girls) can represent the elements, the stars, the planets, even the

divisions of time. Why should they not also represent aspects of political

power? There is in fact such a “political” interpretation of the erotic

poems of the Sixth Dalai Lama by Per K. Sorensen. The author claims that

the poetry of the god-king used the erotic images as allegories: the “tiger

girl” conquered in a poem by the sixth Kundun is supposed to

symbolize the clan chief of the Mongols (Sorensen, 1990, p. 226). The

“sweet apple” or respectively the “virgin” for whom he reaches out are

regarded as the “fruits of power” (Sorensen, 1990, p. 279). Sorensen

reinterprets the “love for a woman” as the “love of power” when he writes:

“We shall tentatively attempt to read the constant allusion to the girl and

the beloved as yet a hidden reference to the appropriation of real power, a

right of which he [the Sixth Dalai Lama] was unjustly divested by a

despotic and complacent Regent, who in actual fact demonstrated a conspicuous

lack of interest in sharing any part of the power with the young ruler”

(Sorensen, 1990, p. 48).

But this is a matter of much more than allegories.

A proper understanding of the tantras instantly

makes the situation clear: the Sixth Dalai Lama was constantly conducting

tantric rituals with his girls in order to attain real power in the state.

In his mind, his karma mudras

represented various energies which he wanted to acquire via his sexual

magic practices so as to gain the power to govern which was being withheld

from him. If he composed the lines

As long as the pale moon

Dwells over the East

Mountain,

I draw strength and bliss

From the girl’s body

(Koch, 1960, p. 172)

- then this was with

power-political intentions. Yet some of his lines are of such a deep

melancholy that he probably was not able to always keep up his tantric

control techniques and had actually fallen deeply in love. The following

poem may indicate this:

I went to the wise jewel, the lama,

And asked him to lead my spirit.

Often I sat at his feet,

But my thoughts crowded around

The image of the girl.

The appearance of the god

I could not conjure up.

Your beauty alone stood before my eyes,

And I wanted to catch the most holy teaching.

It slipped through my hands, I count the hours

Until we embrace again.

(Koch, 1960, p. 173)

A tantric history of

Tibet

The following, Seventh Dalai Lama (1708-1757) was

the complete opposite of his predecessor. Until now no comparisons between

the two have been made. Yet this would be worthwhile, then whilst the one

represented wildness, excess, fantasy, and poetry, his successor relied

upon strict observance, bureaucracy, modesty, and learning. The tantric

scheme of anarchy and order, which the “Great Fifth” ingeniously combined

within his person, fell apart again with both of his immediate successors.

Nothing interested the Seventh Dalai Lama more than the state bureaucratic

consolidation of the Kalachakra Tantra. He commissioned the Namgyal Institute, which still today looks after this

task, with the ritual performance of the external time doctrine. Apart from

this he introduced a Kalachakra

prayer into the general liturgy of the Gelugpa

order which had to be recited on the eighth day of every Tibetan month. We

are also indebted to him for the construction of the Kalachakra sand mandala and the choreography of the complicated dances

which still accompany the ritual.

Anarchy and state Buddhism thus do not need to

contradict one another. They could both be coordinated with each other.

Above all, the “Great Fifth” had recognized the secret: the Land of Snows was to be got the better of

through pure statist authority, it had to be controlled tantricly,

that is, the chaos and anarchy had to be

integrated as part of the Buddhocracy. Applied to

the various Tibetan religious schools this meant that if he were to succeed

in combining the puritanical, bureaucratic, centralizing, disciplined,

industrious, and virtuous qualities of the Gelugpas with the

libertarian, phantasmagorical, magic, and decentralizing characteristics of

the Nyingmapas,

then absolute control over the Land of Snows must be attainable. All the

other orders could be located between these two extremes.

Such an undertaking had to achieve something which

in the views of the time was impossible, then the Gelugpas were

a product of a radical critique of the sexual dissolution and other

excesses of the Nyingmapas.

But the political-religious genius of the Fifth Dalai Lama succeeded in this

impossible enterprise. The self-disciplined administrator upon the Lion

Throne preferred to see himself as Padmasambhava

(the root guru of the Nyingmapas) and declared

his lovers to be embodiments of Yeshe Tshogyal (Padmasambhava’s the

wisdom consort). Tibet

received a ruler over state and anarchy.

The political mythic history of the Land of Snows thus falls into line with a

tantric interpretation. At the beginning of all the subsequent historical

events stands the shackling of the chaotic earth goddess, Srinmo, by the king, Songtsen

Gampo, (the conquest of the karma mudra by the yogi). Through

this, the power of the masculine method (upaya) over the feminine

wisdom (prajna)

invoked in the sexual magic ritual precedes the supremacy of the state over

anarchy, of civilization over wilderness, of culture over nature. The

English anthropologist, Geoffrey Samuel, thus speaks of a synthesis which

arose from the dialectic between anti-state/anarchist and clerical/statist

Buddhism in Tibet,

and recognizes in this interrelationship a unique and fruitful dynamic. He

believes the Tibetan system displays an amazingly high degree of fluidity,

openness, and choice. This is his view of things.

But for us, Samuel is making a virtue of

necessity. We would see it exactly the other way around: the contradiction

between the two hostile extremes (anarchy and the state) led to social

tensions which subjected Tibetan society to an ongoing acid test. One has

to be clear that the tantric scheme produces a culture of extreme dissonance

which admittedly sets free great amounts of energy but has neither led

historically to a peaceful and harmonic society to the benefit of all

beings nor can do so in the future.

Samuel makes a further mistake when he opposes

clerical state Buddhism to wild tantric Buddhism as equal counterpoles. We have shown often enough that the

function of control (upaya)

is the more important element of the tantric ritual, more important and

more steadfast than the temporary letting loose of wild passions. Nevertheless

the contradiction between wildness (feminine chaos) and taming (masculine

control) remains a fundamental pattern of every sexual magic project — this

is the reason that ("controlled”) anarchy is a part of the Tibetan

“state theology” and thus it was never, neither for Atisha

nor Tsongkhapa, the two founding fathers of state

Buddhism, a question of whether the tantras

should be abolished. In contrast, both successfully made an effort to

strengthen and extend the control mechanisms within the tantric rites.

If the “political theology” of Lamaism

applies the tantric pattern to Tibetan society, then — from a metaphysical

viewpoint — it deliberately produces chaos to the point of disintegration

so as to ex nihilo establish law

and order anew. Internally, the

production of chaos takes place within the mystic body of the yogi via the

unchaining of the all-destroying Candali. Through this internal fragmentation the yogi is completely “freed” of his

earthly personality so as to be re-created as the emanation of the

spiritual horde of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and

protective deities who are at work behind all reality.

This inverted logic of the tantras

corresponds on an outwardly level

to the production of anarchy by the Buddhist state. The roaming “holy

fools”, the wild lives of the grand sorcerers (Maha Siddhas), the excesses of the

founding father, Padmasambhava, the still to be

described institution of the Tibetan “scapegoats” and the public debauchery

during the New Year’s festivities connected with this, yes, even the erotic

games of the Sixth Dalai Lama are such anarchist elements, which stabilize

the Buddhocracy in general. They must — following

the tantric laws — reckon with their own destruction (we shall return to

this point in connection with the “sacrifice” of Tibet), then it legitimates

itself through the ability to transform disorder into order, crime into

good deeds, decline and fall into resurrection. In order to implement its

program, but also so as to prove its omnipotence, the Buddhist Tantric state

— deliberately — creates for itself chaotic scenarios, it cancels law and

custom, justice and virtue, authority and obedience in order to, after a

stage of chaos, re-establish them. In other words it uses revolution to

achieve restoration. We shall soon see that the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

conducts this interplay on the world stage.

It nonetheless remains to be considered that the

authority of Tibetan state Buddhism has not surmounted the reality of a

limited dominion of monastic orders. There can be no talk of a Chakravartin’s the exercise of power, of a world

ruler, at least not in the visible world. From a historical point of view

the institution of the Dalai Lama remained extremely weak, measured by the

standards of its claims, unfortunately all but powerless. Of the total of

fourteen Dalai Lamas only one is can be described as a true potentate: the

“Great Fifth”, in whom the institution actually found its beginnings and

whom it has never outgrown. All other Dalai Lamas were extremely limited in

their abilities with power or died before they were able to govern. Even

the Thirteenth, who is sometimes accorded special powers and therefore also

referred to as the “Great”, only survived because the superpowers of the

time, England and Russia, were unable to reach agreement on the division of

Tibet. Nonetheless the institution of the god-king has exercised a strong

attraction over all of Central Asia for centuries and cleverly understood

how to render its field of competence independent of the visible standards

of political reality and to construct these as a magic occult field of

forces of which even the Emperor of China was nervous.

"Crazy wisdom” and the West

Already in the nineteen twenties, the voices of

modern western, radical-anarchist artists could be heard longing for and

invoking the Buddhocracy of the Dalai Lama. “O

Grand Lama, give us, grace us with your illuminations in a language our

contaminated European minds can understand, and if need be, transform our

Mind ...” (Bishop, 1989, p. 239). These melodramatic lines are the work of Antonin Artaud (1896-1948).

The dramatist was one of the French intellectuals who in 1925 called for a

“surrealist revolution”. With his idea of the “theater of horrors”, in

which he brought the representation of ritual violence to the stage, he

came closer to the horror cabinet of Buddhist Tantrism

than any other modern dramatist. Artaud’s longing

for the rule of the Dalai Lama is a graphic example of how an anarchist,

asocial world view can tip over into support for a “theocratic” despotism.

[1]

There was also a close connection between Buddhism

and the American “Beat Generation”, who helped decisively shape the youth

revolts of the sixties. The poets Jack Kerouac, Alan Watts, Gary Snyder,

Allan Ginsberg, and others were, a decade earlier, already attracted by

Eastern teachings of wisdom, above all Japanese Zen. They too were

particularly interested in the anarchic, ordinary-life despising side of

Buddhism and saw in it a fundamental and revolutionary critique of a mass

society that suppressed all individual freedom. “It is indeed puzzling”,

the German news magazine Der Spiegel

wondered in connection with Tibetan Buddhism, “that many

anti-authoritarian, anarchist and feminist influenced former ‘68ers’

[members of the sixties protest movements] are so inspired by a religion

which preaches hierarchical structures, self-limiting monastic culture and

the authority of the teacher” (Spiegel,

16/1998, p. 121).

Alan Watts (1915-1973) was an Englishman who met

the Japanese Zen master and philosopher, Daietsu Teitaro Suzuki, in London. He began to popularize Suzuki’s

philosophy and to reinterpret it into an unconventional and anarchic

“lifestyle” which directed itself against the American dream of affluence.

Timothy Leary, who propagated the wonder drug LSD

around the whole world and is regarded as a guru of the hippie movement and

American subculture, made the Tibetan

Book of the Dead the basis of his psychedelic experiments. [2]

Already at the start of the fifties Allen Ginsberg

had begun experimenting with drugs (peyote, mescaline, and later LSD) in

which the wrathful tantric protective deities played a central role. He

included these in his “consciousness-expanding sessions”. When he visited

the Dalai Lama in India

in 1962, he was interested to know what His Holiness thought of LSD. The Kundun replied with a counter-question, however, and

wanted to find out whether Ginsberg could, under influence of the drug, see